The Fairshare Model: Chapter Eight

Karl M. Sjogren

2015-04-10

By Karl M. Sjogren *

Chapter 8: Macro-Economic Context-Income Inequality

Preview

- Foreword

- Piketty's R > G

- Conservative Perspectives on Income Inequality

- Another Take: R > L

- Common Ground?

- Is the Fairshare Model Capitalism?

- Economic Justice in the New Issue (IPO) Market

- Onward

Foreword

Income inequality--all view it as the handmaiden of slow economic growth. Increasingly, the view has emerged that it also reflects a system that is gamed to favor the wealthy and connected. At another level, it's a discussion about how to promote the best society. It has become a hot-button issue.

The Fairshare Model presents a partial solution, in that the benefits only go to those with "skin in the game"; those who invest in or work for a company that raises capital using the model. This is a narrow group, and, only some who provide capital and labor to companies that use the model will have a good result.

The model's solution is to expand the opportunity for those who rely on the return on their labor to participate in the return on capital. That is, make it easier for non-accredited investors who invest in companies that use the Fairshare Model and those who work for them to earn income from capital gains. It's an idea about how to address income inequality that may have broad political appeal. Not so much for the effect it will have in the next few years, but in a generation or two, once it becomes the New Normal for how companies raise public venture capital.

This solution is discussed at the end of this chapter. Before then, we'll consider the phenomena of rising income inequality from a range of perspectives.

Piketty's R > G

In 2014, French economist Thomas Piketty published Capital in the 21 st Century, which examines how income has been distributed in capitalistic economies. This summary is from The New Yorker : [88]

Using tax records and other data, he studied how income inequality in France had evolved during the twentieth century, and published his findings in a 2001 book. A 2003 paper that he wrote with Emmanuel Saez, examined income inequality in the United States between 1913 and 1998. It detailed how the share of U.S. national income taken by households at the top of the income distribution had risen sharply during the early decades of the twentieth century, then fallen back during and after the Second World War, only to soar again in the nineteen-eighties and nineties.

With the help of other researchers, Piketty expanded his work on inequality to other countries, including Britain, China, India, and Japan. The researchers established the World Top Incomes Database, which now covers some thirty countries. They also updated their U.S. figures, showing how the income share of the richest households continued to climb during and after the Great Recession, and how, in 2012, the top one per cent of households took 22.5 per cent of total income, the highest figure since 1928.

The book's central argument captured considerable attention; that the growth in the size of the Middle Class in the 20 th Century was a historic anomaly, and, rising income inequality is a return to normalcy. In other words, income inequality has been a persistent economic reality. And, the 20 th Century experience of a large and growing Middle Class was a remarkable phenomenon that is unlikely to persist. Professor Piketty uses this formula to explain why:

Return on capital > Growth in the economy

expressed as

R > G

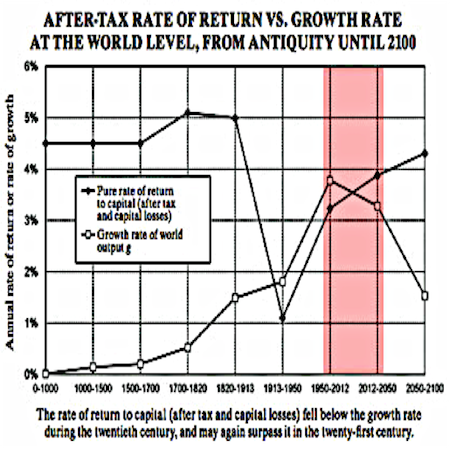

The formula means that the rate of Return on Capital (abbreviated as "R"in the side chart) has tended to exceed the Growth Rate in the Economy (abbreviated as "G"). [89]

Piketty's measurement period is about two thousand years--year 0 to 2012. Over this time, he concludes that R has averaged 4 to 5% per year and G has been about zero, 0.1%.

Over a long period of time, the difference in income magnifies. In part, because it is accumulated, in the form of wealth. In part, because wealth that is invested earns the higher rate of return, R. In contrast, those whose income is chiefly derived from their labor see their income grow at the lower rate, G. Thus, the formula neatly explains why the rich get richer over time. The components of the two rates are identified below.

R = Return on capital = Interest + Dividends + Capital Gains (asset appreciation)

G = Growth in the economy = Productivity Rate X Change in Population Size

The components of R are straight-forward; interest dividends and capital gains. The components of G merit explanation, however.

It's intuitive to associate productivity with growth. When the productivity rate climbs, so does economic growth. The reverse effect is also clear.

Less obvious, is why an increase in population promotes economic growth or why a decrease in population vice versa contributes to a shrinking economy. It happens because people naturally find ways to make economic transactions to support themselves—the best that they can, anyway. An increase in the number of people transacting for food, clothing, shelter and so on contributes to an increase in economic activity. It works the opposite way when population shrinks; a reduction in the number of people making such transactions contributes to a decline in economic growth.

This chart illustrates Piketty's long-view findings about R and G, starting in Year 0 and projected to the end of the current 21 st century. The return on capital after taxes and loss of capital (due to fire, war, spoilage, etc.), R, is the line that begins at the 4.5% mark represents. The line that begins at zero is G, the growth rate of the world's economic output.

Note that time on the horizontal axis is in irregular blocks. [90]

For the first 1,500 years, from year 0 through the Roman Empire and the end of the Middle Ages, the return on capital (R), averages 4.5%. Around 1500, sparked by the discovery of the New World and the European Renaissance, it enjoys a 200 year climb to about 5%. [In the last chapter, 1500 was identified as the start of the Modern Era.] From 1700 to 1820, the birth of Modern Society, it remains steady. Then, it plunges to 1% between 1913 and 1950, the result of the First World War, the Great Depression and the Second World War; capital assets were destroyed or consumed in the wars and devalued in the interwar period.

Turn now to the economic growth rate (G). It hovers above zero from year 0 to 1500, an epoch defined by rising agricultural productivity and growth in mercantile trade. It climbs significantly, up to 0.5% over the first 320 years of the Modern Age (1500 to 1820). Then, with dawn of Modern Societies and Modern Economies, it triples to 1.5%. This is the start of what Edmund Phelps—based on unrelated analysis—characterized as an age of mass flourishing. Pushed by productivity improvements that emerge during the Industrial Revolution, economic growth continues to increase to nearly 2% before WW I. Note that for the first time, G exceeds R; economic growth is greater than the return from capital by about 0.75% per year.

During the postwar period, 1950 to 2012, R and G climb nearly in tandem. Economic growth is nearly one percent higher than the return on capital in 1950, but the advantage erodes by 2012. More significantly, economic growth, the factor that enabled the formation of a large and growing Middle Class in America, grows to about 3.9%, a historic high.

Piketty speculates how these trends will play out over the 21st century. Absent adoption of tax policies that tax capital gains and inherited wealth at higher rates, or, tax rates on income from salaries and wages at lower rates, he thinks that it's likely that R, the return on capital, will begin to exceed G, economic growth. This occurs in the shaded portion of the graph, midway between 2012 and 2050.

After that, between 2050 and 2100, his model shows the return on capital will continue to grow toward the pre-Renaissance norm. And, economic growth will slide from its 2012 peak of 3.8% to the 1.5% last seen before 1820 (i.e., the start of modern economies).

He anticipates rapid expansion in the use of non-human producers of economic output—computers, robots or biological processes—plus, decline in population size. Absent changes in tax policies, Piketty expects that the economic benefits generated by non-human forms of production will disproportionately go to the owners of capital.

With respect to his historic analysis, economists on all points of the political spectrum express admiration. Some disagree with his dystopian projection for labor and there is a predictable divide on his prescription for higher taxes on the wealthy. Piketty reports that Microsoft founder Bill Gates told him "I love everything that's in your book, but I don't want to pay more tax."Recognizing the charitable work that the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation does, and the efficiency with which it operates, Piketty said "I understand his point. I think he sincerely believes he's more efficient than the government, and you know, maybe he is sometimes." [91]

In his personal blog, Gates encourages others to read Piketty's book or a good summary. [92] Below are some of the points that he makes in the full piece:

"I [Bill Gates] agree with Piketty's most important conclusions, and I hope his work will draw more smart people into the study of wealth and income inequality. I very much agree that:

- High levels of inequality are a problem—messing up economic incentives, tilting democracies in favor of powerful interests, and undercutting the ideal that all people are created equal.

- Capitalism does not self-correct toward greater equality—that is, excess wealth concentration can have a snowball effect if left unchecked.

- Governments can play a constructive role in offsetting the snowballing tendencies if and when they choose to do so.

Extreme inequality should not be ignored—or worse, celebrated as a sign that we have a high-performing economy and healthy society. Yes, some level of inequality is built in to capitalism. The question is, what level is acceptable? And when does it do more harm than good? That's something we should have a public discussion about, and it's great that Piketty helped advance that discussion in such a serious way.

At the core of his book is a simple equation: r > g, where r stands for the average rate of return on capital and g stands for the rate of growth of the economy. The idea is that when the returns on capital outpace the returns on labor, over time the wealth gap will widen between people who have a lot of capital and those who rely on their labor.

Other economists have cast doubt on the value of r > g for understanding whether inequality will widen or narrow. I'm not an expert on that question. What I do know is that r > g doesn't adequately differentiate among different kinds of capital with different social utility.

I agree that taxation should shift away from taxing labor. It doesn't make any sense that labor in the United States is taxed so heavily relative to capital. It will make even less sense in the coming years, as robots and other forms of automation come to perform more and more of the skills that human laborers do today.

But rather than move to a progressive tax on capital, as Piketty would like, I think we'd be best off with a progressive tax on consumption. Like Piketty, I'm also a big believer in the estate tax. Letting inheritors consume or allocate capital disproportionately simply based on the lottery of birth is not a smart or fair way to allocate resources.

The debate over wealth and inequality has generated a lot of partisan heat. Even with its flaws, Piketty's work contributes at least as much light as heat. And now I'm eager to see research that brings more light to this important topic."

Conservative Perspectives on Income Inequality

Writing in the New Republic in November 2013, liberal journalist Timothy Noah summarized the view of conservatives on income inequality this way. [93]

The usual conservative approach to income inequality (besides simply ignoring it) is to try to argue that it doesn't really exist, or to argue that if it does exist, it's mooted by upward mobility, or to argue that it's good for you .

Noah seems to be re-purposing conservative talking points about climate change. Nonetheless, conservatives may find his summation suspect, since he's not one of them. Mathew Continetti, however, a journalist with established conservative bona fides. In a Nov. 14, 2011 article Weekly Standard called "About Inequality", he concedes that the inequality trend is probably real, and that it's a nasty business. He just doesn't think it's the government's place to do anything about it. Here's what Continetti had to say: [94]

The way out is to reject the assumption that government's purpose is to redress inequalities of income. Inequalities of condition are a fact of life.

Some people will always be poorer than others. So too, human altruism will always seek to alleviate the suffering of the destitute.

There is a place for reasonable and prudent actions to improve well-being. But that does not mean the entire structure of our polity should be designed to achieve an egalitarian ideal.

Such a goal is fantastic, utopian even, and one would think that the trillions of dollars the United States has spent in vain over the last 50 years to promote 'equality as a fact and equality as a result' would give the egalitarians pause.

Another conservative thinker, Charles Murray of the American Enterprise Institute, expressed a somewhat different perspective in his 2012 book, Coming Apart: The State of White America . In a review of the book called "A Conservative Take on America's Economic Divide", Niall Ferguson wrote: [95]

Murray is no apologist for Wall Street.

Looking at the explosion in the value of the total compensation received by the chief executives of large corporations, he pointedly asks if "the boards of directors of corporate America—and nonprofit America, and foundation America—[have] become cozy extended families, scratching each others' backs, happily going along with a market that has become lucrative for all of them, taking advantage of their privileged positions—rigging the game, but within the law."

In his January 2012 review of Charles Murray's book, New York Times columnist David Brooks wrote: [96]

I'll be shocked if there's another book this year as important as Charles Murray's "Coming Apart."I'll be shocked if there's another book that so compellingly describes the most important trends in American society. Murray's basic argument is not new, that America is dividing into a two-caste society. What's impressive is the incredible data he produces to illustrate that trend and deepen our understanding of it.

His story starts in 1963. There was a gap between rich and poor then, but it wasn't that big. A house in an upper-crust suburb cost only twice as much as the average new American home. The tippy-top luxury car, the Cadillac Eldorado Biarritz, cost about $47,000 in 2010 dollars. That's pricey, but nowhere near the price of the top luxury cars today.

More important, the income gaps did not lead to big behavior gaps. Roughly 98 percent of men between the ages of 30 and 49 were in the labor force, upper class and lower class alike. Only about 3 percent of white kids were born outside of marriage. The rates were similar, upper class and lower class. Since then, America has polarized. The word "class"doesn't even capture the divide Murray describes. You might say the country has bifurcated into different social tribes, with a tenuous common culture linking them.

The upper tribe is now segregated from the lower tribe. T oday, Murray demonstrates, there is an archipelago of affluent enclaves clustered around the coastal cities, Chicago, Dallas and so on. If you're born into one of them, you will probably go to college with people from one of the enclaves; you'll marry someone from one of the enclaves; you'll go off and live in one of the enclaves.

Worse, there are vast behavioral gaps between the educated upper tribe (20 percent of the country) and the lower tribe (30 percent of the country). This is where Murray is at his best, and he's mostly using data on white Americans, so the effects of race and other complicating factors don't come into play.

Roughly 7 percent of the white kids in the upper tribe are born out of wedlock, compared with roughly 45 percent of the kids in the lower tribe. In the upper tribe, nearly every man aged 30 to 49 is in the labor force. In the lower tribe, men in their prime working ages have been steadily dropping out of the labor force, in good times and bad. People in the lower tribe are much less likely to get married, less likely to go to church, less likely to be active in their communities, more likely to watch TV excessively, more likely to be obese.

Murray recommends that the upper tribe be more outspokenly judgmental about non-productive behaviors of the lower tribe, and, that they reduce their self-imposed geographic isolation of living in wealthy enclaves or "Super Zips"(the 900 or so zip codes of affluent communities).

Fast forward two years. A stubbornly slow economic recovery, building resentment over the bank bailouts early in the Great Recession, Occupy Wall Street protests and numerous other indicators of widespread anxiety about the future and dissatisfaction about the-way-things-are-done have come to the forefront of public discussion. Consider this excerpt from David Brook's 2014 column, "The Inequality Problem". [97]

Suddenly the whole world is talking about income inequality. But, as this debate goes on, it is beginning to look as though the thing is being misconceived. The income inequality debate is confusing matters more than clarifying them, and it is leading us off in unhelpful directions.

In the first place, to frame the issue as income inequality is to lump together different issues that are not especially related.

Second, it leads to ineffective policy responses.

Third, the income inequality frame contributes to our tendency to simplify complex cultural, social, behavioral and economic problems into strictly economic problems.

Fourth, the income inequality frame needlessly polarizes the debate.

There seems be little argument that income inequality has been growing and that it presents a threat to the well-being of society in America and elsewhere. On Fox News, whose audience is reliably conservative, media pundit Howard Kurtz said the following in January 2015: [98]

Suddenly leading Republicans are openly embracing the notion that income inequality is a clear and present danger that must be addressed. That is such a tectonic shift that it moves the national debate several degrees to the left.

It's not that congressional Republicans are going to pass sweeping legislation to boost the income of the lower and middle classes. But it tells you something about how they read the mood of the country. What agile politicians do is try to coopt issues that the other side views as strengths. Real change is often preceded by an evolution in the way politicians frame an issue.

In the past, when Democrats pounded away at the gap between rich and poor, many Republicans accused them of class warfare. Obviously, the GOP would explore a different mix of incentives and reject pitches to tax the rich and Wall Street to finance lower levies for the middle class. But after being pilloried as the party of the 1 percent, several of its biggest names are now saying the 1 percent have too much of the pie.

The question is, what initiatives to reduce income inequality will Republicans support? After all, they now control the legislative branch.

Another Take: R > L

Like many, I've contemplated the relationship between the distribution of wealth/income and social/political stability. Piketty provides scholarly evidence that income inequality is increasing and insight as to why.

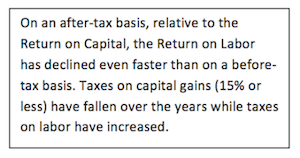

Coincidently, before Piketty's book came out, I had formulated an explanation for income inequality and a formula that is remarkably similar to his. I think it has been increasing because the return on capital exceeds the "return on labor."I express the idea in this concept formula:

Return on Capital > Return on Labor

expressed as

R > L

My R is the same as Piketty's. My "L"is the "Return on Labor", which is a bit different from Piketty's G. To measure it, one might take real wages (i.e., inflation-adjusted) and add proxies for a sense of security, belonging, and purpose. [99] These senses are a bit nebulous, but so too are "consumer confidence"and "investor sentiment,"both of which are regularly commented on. The Return on Labor is this sort of measure; a somewhat quantifiable, but largely sensed, read of the broad population's sense of economic vitality and optimism. Ultimately, I see L as a barometer of social stability.

Utilizing "economic impressionism"(i.e., relying more on observation and contemplation than on data), I surmised that the Return on Labor has been in decline, relative to the Return on Capital. And, the phenomenon gained traction in the 1980s due to significant expansion in the population available to perform labor-intensive work.

The adoption of export oriented policies by China, India and other countries ushered in a new age for labor-intensive products and services on markets worldwide.

In 1991, the Soviet Union dissolved. Russia, along with China, puzzled on how to transition from a centrally controlled economy to one that was more market oriented, while minimizing political instability. [100] President George H. W. Bush proclaimed "A New World Order"was emerging. He was conveying optimism about the future. But the battle for the commanding heights of the world economies merely shifted from one based on political ideology to one driven by market economies. [101]

The formation of the European Union in 1992 had a similar effect in Europe because products made in member countries that had low labor cost could enter those with high labor cost without restriction or taxes. In the U.S., trade agreements with Canada, Mexico and other countries added to the effect. "Globalization"was coined to describe what was going on, increasing integration of economies around the world.

Theses changes created a new world order for the Return on Labor, for increasingly, labor was becoming a commodity. Labor intensive industries like textiles and furniture were among the first to be affected but capital intensive industries like tires and steel followed because reducing the variable cost of labor positioned them to cover their fixed costs faster. [102] Few markets were unaffected.

Computer and telecom technologies extended the impact to all manner of service sector jobs. Not only were there off-shore call centers to handle customer support, there were radiologists in distant lands who competed to evaluate the x-ray image taken at the local hospital.

The Return on Labor diminished not just because of competition from people in distant lands. It happened as technologies spawned more efficient ways to perform work. Industries characterized by concentration of economic power increasing saw challenges by upstarts. The rise of portable, networked computers reduced the demand for office secretaries that typed and organized correspondence. Farmers, manufacturers and service providers adopted technologies that made them more effective; in part, by using labor more efficiently.

New business models deteriorated the Return on Labor too. Sometimes, regulatory reform led to new business models. Often, they arose from new technologies, but they were always driven by innovative thinking. For example, Big Box retailers emerged who displaced local merchants by combining their access to products made in low-cost markets, sophisticated supply-chain technology and new business strategies. Travel, newspapers, and book publishing and distribution were similarly transformed.

The bottom line is that very few markets avoided movement toward making labor a commodity.

Consumers were winners, however-they got lower prices.

So too were companies that reduced their cost of labor (i.e., wages, benefits).

Investors who made good bets on innovators saw the value of their investment climb; those who hung onto shares in non-innovative firms saw losses. [103]

The losers were workers and suppliers who were not competitive. Those who remained competitive had higher insecurity because their world could change quickly.

Common Ground?

Liberals and conservatives agree that income inequality is real and a problem. That suggests that policy makers will agree on some steps to address it. Tax policy is the obvious tool, but it's also a contentious one and vulnerable to being defined by self-serving political interests.

With the Fairshare Model, I propose an additional path to explore, one that should appeal to those whose politics are on the left, center and right. I dub it the "Paul McCartney Solution"because his song "Let Em' In"captures the idea—expand the opportunities for workers to earn the return on capital. Besides, everyone likes Sir Paul.

The Fairshare Model helps workers get in on the higher return on capital in two ways:

1. It helps small investors to invest in venture stage companies at lower valuations. They don't have many attractive opportunities to earn a return on their capital; they rely on the return on their labor. A lower valuation reduces the cost of a position (e.g. a hundred shares will cost less). This, in turn, increases the return of a good investment and reduces the cost of a losing one. It also makes it easier to diversify a venture-stage portfolio and increased diversification reduces portfolio risk.

2. Employees "capitalize"the value of their collective performance when Performance Stock converts. Without having to risk capital, they can earn a capital gain as a result of their labor.

The ability of the Fairshare Model to ameliorate income inequality will take generations to test because the outcome of companies that adopt the model will take years to play out. Not only that, it will only pay off for those who invest in or work for a successful venture. Therefore, it is not a general panacea.

Still, it's something to contemplate. Policy makers chart a course to where they want the economy and society to be in a few decades. To the extent the Fairshare Model is part of that vision, it's a vote for an entrepreneurial economy that offers opportunity for the 99%. Meanwhile, the model has clear potential to benefit the capital-starved start-up sector, which has a clear record of spawning economic growth and job creation.

Reflect how much money might be channeled to these two groups of workers—small investors and employees in the companies that they invest in. If the Fairshare Model is used by public companies that trade on large exchanges; the capital gains earned by employees could rival the return that hedge funds deliver to their investors…billions of dollars! Some of these funds profit from trading ahead of average investors, sometimes on inside information. In the Fairshare Model, when favorable developments result in Performance Stock conversions, some of the upside that a fund would normally reap will be redirected to employees.

Is the Fairshare Model Capitalism?

Some have told me that the Fairshare Model smacks of communism or socialism. I find this odd. The most basic reason is that those models share wealth at the macro-economic level while the Fairshare Model shares it at the micro-economic level, between those who provide capital and those who provide the labor that make the capital worth more. Put simply:

Karl Marx said "From each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs."

Karl Sjogren says "Fairly share the rewards of backing a venture-stage company between those who provide capital and those who make it worth more by virtue of their labor."

The Fairshare Model is not designed to address income inequality. It is designed to give public investors a deal that is comparable to what a VC would get. Doing so improves the opportunity for a return on capital for IPO investors that based on supporting the company, not getting in front on a Wall Street orchestrated "pop."It also creates an opportunity for employees to earn the return on capital for their labor.

Enabling employees to earn the return on capital for their labor (via Performance Stock conversions) is effectively a Rorschach test that reveals ones deep sensibilities about the relationship between capital and labor.

A favorable response to the Fairshare Model will come from people who support ways to make capitalism work better for more people. They will see micro-economic benefits to companies, investors and workers from a better alignment between investors and employees. They will see macro-economic benefits for a nation too. In part, because of the amount of money that could be redirected from secondary market traders to workers, once the Fairshare Model becomes the New Normal. They will also see a psychological benefit in that the model will inspire a venturesome spirit—boost an economy's sense of vitalism, described in the last chapter. Put another way, it will feed a society's "animal spirits", the term coined by economist John Maynard Keynes to describe the confidence, the emotional mindset, to invest or spend.

The Fairshare Model will be evoke a skeptical, and possibly hostile, response from some people. They will include traditionalists and those who think that the human behavior challenges (i.e., the ability to cooperate) that must be addressed will be not worth the effort. A negative reaction may come from those who aspire to profit from the-way-things-are-now because the Fairshare Model goes into the belly of the beast, into the DNA of capitalism—valuation—and presents a radically different vision for how way to address it. Of course, there are such folks who will favor a fairer variant of capitalism. Finally, there will be those who see bets on valuation as the essence capitalism; they will have trouble with an effort to loosen the risk of setting a valuation from the risk of delivering performance. [104]

I look forward to engaging skeptics, because their questions will focus attention on matters that are better to confront before the Fairshare Model has its initial tests. To traditionalists, I simply say that the Fairshare Model strengthens virtuous aspects of capitalism by encouraging the allocation of reward based on merit and it does so by summoning stronger market forces.

Incidentally, John Maynard Keynes and Edmund Phelps are not the only economists to focus on the "animal spirits"an economy. In 2009, George A. Akerlof [105] and Robert J. Shiller, each of whom is a winner of the Nobel Prize, published Animal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy and Why It Matters for Global Capitalism . The Economist described its take-away points as follows: [106]

- Conventional economic analysis confines itself to rational, quantifiable facts. However, economic decision makers are often intuitive, emotional and irrational.

- Confidence or lack of it can drive or hamper economic growth.

- Fairness matters greatly in setting wages, but classical economic models ignore it.

- People tend to reach irrational conclusions about money; this is the "money illusion."For example, they ignore inflation and believe their savings maintain their value; or they resist pay cuts when prices fall - even if their jobs may be at stake.

- Stories of corruption and broken trust can contribute to economic depressions.

- Minorities have a different story of America than whites do. Their story depicts an unfair society offering less opportunity than the majority perceives.

- Economists and policymakers need to shed the untenable theory of rational, efficient, self-correcting markets and pay appropriate attention to animal spirits.

Economic Justice in the New Issue (IPO) Market

The Fairshare Model offers an approach to the income inequality problem for a narrow communities of interest. It is not a solution for a nation. Some readers will appreciate the comparison to a city-state versus a nation. Before the formation of nation-states, humans organized their affairs in autonomous city-states. Today, Vatican City and Monaco are city-states and Hong Kong has historically been one. The states or provinces that now comprise nations reflect a city-state origin.

The community of interest I have in mind is not defined by geography. It is comprised of people buy the IPO stock of a venture-stage company, and, people who work for such a company. It will be easier to find broad support for steps that address income inequality for this narrow group than for an entire nation. Such a focused approach may appall some who want to see a comprehensive solution, but, it is in keeping with the fractured nature of society today and reflects political realism.

The Fairshare Model is not a cure for broad income inequality but it is a solution for a micro-economic problem for investors and entrepreneurs—how to value a venture-stage company when it sells its stock to the public. The model straddles two communities of interest in an issuer's sphere. Those who provide it with capital and those who provide it with labor. It frames a relationship whereby each can benefit from the other. The providers of capital get a low valuation. Those who provide labor get the capital they need to build a company and an upside if they perform. The contribution to reducing income inequality is that many people who will have interest in the IPO shares of a company that adopts the Fairshare Model will be unaccredited investors, as will be most of those who work for the company. Indirect benefits will flow to the communities where such companies are located. And, as the company performs, it generates opportunity for others. Essentially, the model promotes mass flourishing and more competitive capitalism (versus corporatism or crony capitalism). There is a lot to like, regardless of where one is on the political spectrum.

In Mass Flourishing, Edmund Phelps writes about the late John Rawls, former colleague of his, and his writings on economic justice. He offers this quote from Rawls' 1971 work, A Theory of Justice that: [107]

A society is a cooperative venture for mutual advantage….There is an identity of interests, since social cooperation makes possible a better life for all than any would have if each were to live solely by his own efforts. There is a conflict of interests, since persons are not indifferent as to how the greater benefits produced by their collaboration are distributed, for in order to pursue their ends they each prefer a larger to a lesser share. A set of principles is required for choosing among the various social arrangements which determine this division of advantages and for underwriting an agreement on the proper distributive shares. These…are the principles of social justice.

Phelps then writes "The classic defenders of capitalism…have sought an economy having few "interferences"with what they see to be the good in capitalism—the 'freedoms' and the 'growth'—without a thought for what a just economy is. In the premise of some of these classic defenders, each participant receives in pay the value of his or her contribution to the national product, exactly as if each worked in isolation, so it is difficult if not impossible to see what moral claim one sort of participant might have to the pay of other sorts. But this premise is untenable." [108]

He adds that other defenders of capitalism "while conceding that the low earners benefit the high earners, jump in to say that the high earners, through their capital investment and innovation, greatly benefit the low earners—puling up their wages and employment. They see no reason why the high earners should dig into their pockets to pay subsidies aimed at further benefiting the low earners. But this view of a market economy is as mistaken as the previous one. The free market sets wages that send signals and present incentives serving efficiency —in some rough and ready way, at any rate- not any ideas of equity ." [109]

The preceding comments were about after-tax wages in an economy. How might these ideas on economic justice apply to the IPO market? Phelps doesn't focus on that, but he sets up that question when he notes that "A modern economy is striking for the extraordinary income —oversize profits and capital gains in anticipation of profits-that accrues to those whose new idea or whose entrepreneurial development or marketing of a new idea led to a successful adoption in the marketplace." [110] He seems to be describing the high-outsized, in many cases-valuations associated with venture-stage companies that represent wealth delivered today in anticipation of future performance .

As chapter three The Problem With a Conventional Capital Structure considered, the capital formation process that begins with a VC investment and ends with a Wall Street IPO is constructed in a manner that has considerable disadvantage for public investors…and can disadvantage the angel investors who come in before a VC. Advantage in this allocation of wealth is based on efficiency-and market power—not based on any ideas of equity or economic justice.

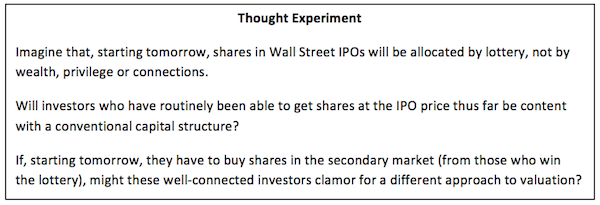

Put another way, for a given company, if you are a VC, your dollar buys you more than an angel investor's dollar does, because you get better terms. And, if you are privileged enough to get an allocation of shares in a Wall Street IPO, your dollar gets a better deal than the average investor waiting to buy shares in the secondary market. That is, the deal you get is based on who you are more than the company's performance.

Rawls identified two principles that would lead to a just and moral society. The first is that each person have liberty that is compatible with the liberty of others. The second is that social and economic positions be designed to everyone's advantage and open to all. In other words, Rawls said economic justice improves when open opportunity expands and corporatism—rules and practices that privilege certain players—is reduced. He conducted experiments in which study subjects were told they would play a social-economic game after they defined the rules. When participants knew in advance what their position in the game would be, they advocated rules that benefited someone in that position. When they did not know what position they would occupy, they designed rules that did not favor any type of player over another. Rawls allowed that a justly functioning system could have unjust outcomes-he found that participants based their assessment of the fairness of the system based on whether it appeared to be a justly functioning, not on the outcome.

Now, with all this in mind, reflect on the thought experiment about Wall Street IPO allocations that was at the end of chapter three.

The Fairshare Model focuses on valuation; making it more fair, more driven by actual performance than by speculation about fleeting Next Guy economics. Imagine that those who now occupy a preferred position in the current capital formation process had to redesign it in a Rawlsian thought experiment. The study participants would include entrepreneurs, angel investors, VCs, underwriters and their favored customers for IPO allocations and average investors. No person designing the process would know in advance what position they would occupy in the game. So, someone who was actually a VC or entrepreneur, might be a public or angel investor in the game. Or, an underwriter might be an entrepreneur or public investor.

I think that the rules for valuation and share allocation that would emerge from such an experiment would resemble the Fairshare Model, don't you?

When a well-performing company adopts the Fairshare Model, there are more winners. But who loses? The largest group, I suspect, will be traders in the secondary market. Those who "buy on the rumor and sell on the news", or, buy on talk of performance and sell when it is announced. They lose in the Fairshare Model because a significant portion of the increase in the market capitalization that results from actual performance goes to those who delivered the performance…the company's employees.

Arguably, this is consistent with a justly functioning—and well functioning—system because while speculators provide something useful, liquidity, they don't invent or make anything and they don't provide the capital to those that do.

Onward

The next chapter considers how the dynamics of the Fairshare Model promotes a new vector of economic competition…the ability to cooperate.

[88] Forces of Divergence, By John Cassidy, The New Yorker, Mar. 31, 2014 http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/03/31/forces-of-divergence

[89] The PBS News Hour used this chart to explain Piketty's theory in its May 2014 report "Gaming Mr. Darcy: What Jane Austen Teaches Us About Economics" http://www.pbs.org/newshour/making-sense/gaming-mr-darcy-what-jane-aust/ . The News Hour also has a left-leaning and right-learning economist debate Piketty's theory in "Why do the rich get richer?"at http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/piketty-takes-on-inequality-in-capital/

[90] The first vertical line marks returns between year 0 and 1000 (1,000 year period). Subsequent ones marks returns between 1000 and 1500 (500 years later), between 1500 and 1700 (200 years later), between 1700 and 1820 (120 years later), between 1820 and 1913 (97 years later); between 1913 and 1950 (47 years later); and between 1950 and 2012 (62 years later) before projecting the balance of this century.

[91] "Thomas Piketty: Bill Gates Told Me He Doesn't Want To Pay More In Taxes", by Maxwell Strachan, Jan. 05, 2015, Huffinton Post, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/01/04/piketty-bill-gates_n_6413446.html

[92] "Why Inequality Matters", by Bill Gates, Oct. 13, 2004, http://www.gatesnotes.com/Books/Why-Inequality-Matters-Capital-in-21st-Century-Review

[96] "The Great Divorce", by David Brooks, Jan. 30, 2012, New York Times, http://nyti.ms/127CFJT

[97] "The Inequality Problem", by David Brooks, Jan. 16, 2014, New York Times, http://nyti.ms/19y4XIh

[98] "The GOP's 2016 playbook? Republicans rip income inequality" http://www.foxnews.com/politics/2015/01/22/gop-2016-playbook-republicans-rip-income-inequality/

[99] I had this notion before learning about the Good Life that Edmund Phelps describes.

[100] A fundamental question was whether to redistribute state-owned property (everything was state-owned), then deregulate prices? Or, deregulate prices and then redistribute property? Russia opted for the former. China chose the latter approach, but controlled price increases in order to minimize social disruption.

[101] An insightful examination of how the 20 thCentury progressed to globalization is provided by Daniel Yergin and Joseph Stansilaw in their 2002 book "The Commanding Heights: The Battle for the World Economy"A PBS program based on the book can be streamed here http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/commandingheights/hi/story/index.html

[102] Governments in these emerging exporters also had weak environmental laws, subsidized business operations and managed currency exchange rates to provide a cost advantages.

[103] "Buy and hold stock for the long term"increasingly sounded like quant advice.

[104] These types are likely to enjoy a sporting event more if they know the betting spread set by odds makers.

[105] Akerlof is married to Janet Yellen, who is chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank.

[107] Mass Flourishing, pages 289

[108] Mass Flourishing, pages 289

[109] Ibid, pages 290

[110] Ibid, page 293

Karl M. Sjogren *

Contact Karl Sjogren is based in Oakland, CA and can be contacted via email or telephone:

Karl@FairshareModel.com

Phone: (510) 682-8093

The Fairshare Model Website

A native of the Midwest, Karl Sjogren spent most of his adult life in the San Francisco Bay area as a consulting CFO for companies in transition—often in a start-up or turnaround phase. Between 1997 and 2001, Karl was CEO and co-founder of Fairshare, Inc, a frontrunner for the concept of equity crowdfunding. Before it went under in the wake of the dotcom and telecom busts, Fairshare had 16,000 opt-in members. Given the rising interest in equity crowdfunding and changes in securities regulation ushered in by the JOBS Act, Karl decided to write a book about the capital structure that Fairshare sought to promote….”The Fairshare Model”. He hopes to have his book out in Spring 2015. Meanwhile, he is posting chapters on his website www.fairsharemodel.com to crowdvet the material.

Material in this work is for general educational purposes only, and should not be construed as legal advice or legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances, and reflects personal views of the authors and not necessarily those of their firm or any of its clients. For legal advice, please consult your personal lawyer or other appropriate professional. Reproduced with permission from Karl M. Sjogren. This work reflects the law at the time of writing.