The Fairshare Model: Chapter Two

Karl M. Sjogren

2015-04-10

By Karl M. Sjogren *

Chapter 2: The Fairshare Model

Preview

- Foreword

- Vision

- Goal

- Problem

- The Fairshare Model

- Thesis

- A Bird's Eye View of the Thesis

- Brief Question & Answer

- What is a public offering?

- How expensive is a public offering?

- What is venture capital?

- What is a venture stage company?

- Is the Fairshare Model "crowdfunding"?

- What is a Capital Structure?

- What is a "class"of stock?

- "Investor Stock", "Performance Stock"…what are these names?

- What is a conventional capital structure?

- Is a stock option that vests based on performance the equivalent of Performance Stock?

- How is performance defined and measured?

- Who gets the Performance Stock?

- Has the Fairshare Model (or anything like it) been used before?

- Do securities laws have to change to make the Fairshare Model legal?

- What is the attraction of the Fairshare Model for public investors?

- What kinds of companies might want to use the Fairshare Model?

- What is the attraction of the Fairshare Model for a company's private investors?

- What is the bargain between a Fairshare Model company and its investors?

- What is the bargain between the company and its workforce?

- How does a stock option compare to an interest in Performance Stock?

- What challenges does the Fairshare Model face?

- Fairshare Model Principles

- Onward

Foreword

This chapter presents the Fairshare Model.

Vision

My vision for the Fairshare Model is that Middle Class investors will be able to make venture capital investments on terms comparable to those that professional investors get.

Goal

My goal is a deal structure that will:

1. Expand entrepreneur access to capital.

2. Offer liquidity to wealthy angel investors who support private companies.

3. Create an attractive yet prudent option for middle class investors to be "mini angel"investors.

Note the self-renewing cycle here. Entrepreneurs are more likely to attract capital if investors feel fairly treated for the risks they assume. Angel investors are more likely to invest in a private company when they believe it can attract investors to the next round of capital, and, there is the prospect of liquidity (the ability to sell shares). Public investors are more likely to provide that capital and liquidity if they, too, feel fairly treated.

Within a generation, I hope that the Fairshare Model will seen as a viable and attractive approach for companies that raise venture capital in a public offering. This will happen if it helps them raise capital (because investors like it) and also gives them a competitive advantage in attracting employees and managing them because, after all, employees ultimately have a great deal to do with the long-term success of a venture.

Problem

As discussed in chapter three, a conventional capital structure is a weak model for a self-renewing cycle of capital. It's fundamental weakness is the need to place a value on future performance anytime new equity capital is raised. This is hard to do, but a conventional model demands that it be done.

To use game theory, entrepreneurs and accredited investors structure their relationship to be a win-win proposition with traces of a zero-sum game. A zero-sum game has a winner and a loser. Once a company goes public, the win-win construct evaporates and zero-sum elements dominate. This happens even though the company is still largely unproven. So, the problem is that a conventional capital structure calls for a zero-sum game for public investors. The Fairshare Model offers a new game formulation. It extends the win-win game to include IPO investors.

The Fairshare Model

The Fairshare Model is for a company (an "issuer") that raises venture capital via a public offering.

There are two classes of stock.

One can trade, the other cannot; both can vote.

I refer to the tradable stock as Investor Stock ; it is sold to investors to raise equity capital for the company.

I refer to the non-tradable stock as Performance Stock ; it is issued to employees, consultants, directors and others.

Investor Stock always has at least 50% of the voting power, even if it represents less than 50% of the total shares issued.

Early on, there will be far more Performance Stock than Investor Stock, at least 5 times more.

But, Investor Stock has at least half the voting power. So, even if Performance Stock is 80% of the total, Investor Stock controls 50% of vote.

If Performance Stock is less than 50% of total shares, voting is on an issued share basis, not on a class basis. So, if Performance Stock represents 40% of total shares, it has 40% of the vote.

Based on quarterly measurements of performance, portions of Performance Stock may convert to Investor Stock.

Note that shareholders of Performance Stock that converts to Investor Stock have the same interests as other Investor Stockholders.

The offering document or prospectus describes the performance criteria. It may be modified by agreement of the Investor Stock and Performance Stock.

Under most circumstances, an offer to acquire the company must be approved by both classes of stock. This may result in accelerated conversion of Performance Stock.

Thesis

Capital markets provide capital to entrepreneurs and liquidity for accredited investors. Middle class investors, however, don't have an attractive, prudent way to invest in young companies.

The opportunity to innovate in this space presents itself when one considers venture capital from the perspective of public investors. Normally, it's viewed from the perspective of venture capitalists, wealthy investors, Wall Street and companies.

This new pathway—the Fairshare Model—treats IPO investors as venture partners as opposed to inhabitants at the bottom of the capital market food chain. To treat public investors as partners, more attention must be paid to valuation.

Early stage companies are hard to value because virtually all their value comes from future performance; which is steeped in uncertainty. A conventional capital structure demands that a value be placed on future performance each time there is an equity financing. Professional venture capitalists skirt this problem by securing deal terms that will retroactively lower their buy-in valuation if expectations are not met. Public investors don't get similar protection when they buy shares in a public venture-stage company, plus, they buy-in at far higher valuations.

For public investors, many of whom are valuation-unaware, the risk of buying stock at an excessive valuation will magnify when the JOBS Act is fully implemented. That is because more companies will seek capital from them. [12] The risk of harm can be mitigated by enhancing valuation awareness. The risk can also be reduced with the Fairshare Model because it side-steps the need to value future performance.

The model was conceived to solve a micro-economic problem—how to enable public investors to invest on terms comparable to VCs. Sometimes, a solution to a specific problem has broader implications for problems that it wasn't designed to address. That's the case with the Fairshare Model. It wasn't created to address the macro-economic challenges of slow growth and rising income inequality, but it offers new perspective on how to address them, in part. In other words, the Fairshare Model reimagines capitalism.

For companies, its promise is twofold. First, it will be easier to raise equity capital in a public offering if investors recognize that they get a better deal than they do from a conventional capital structure. Second, it will provide companies with a competitive advantage when recruiting and managing human capital.

A Bird's Eye View of the Thesis

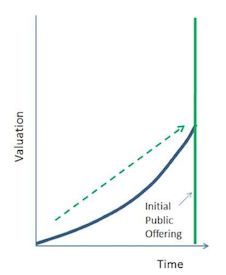

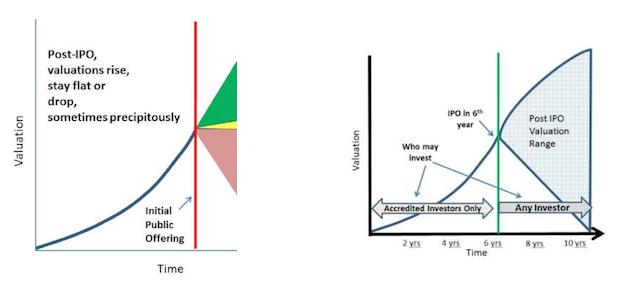

The next few charts illustrate what the valuation curve often looks like for a company that uses a conventional capital structure.

When a conventional capital structure is used, what drives the increase in valuation that often occurs as a company approaches its IPO.

Is it performance or something else?

From the perspective of public investors, what are the risks that the IPO valuation presents?

Under securities law, only accredited investors may invest in a private company.

Companies tend to be valued higher when they are public. Private companies rise in value as expectations of a public offering heighten.

In this chart, the company has its IPO in its sixth year. However, if it were sooner, the valuation curve would look similar.

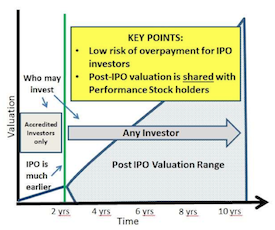

The Fairshare Model is a capital structure designed to encourage companies offer public venture capital investors a private venture capital valuation. In the illustration below, the issuer goes public sooner, in year two, at a much lower valuation. If it performs, the increase in valuation is shared by the investors and employees. [13] If it doesn't perform, public IPO investors lose less because the valuation was lower.

The incentive for the issuer to offer a lower valuation?

A well-performing team can own more of the company than they would if a VC backed them. Plus, they can be more competitive in attracting and managing human capital.

To be clear, the Fairshare Model is designed with public investors in mind. These are largely small investors, also known as average, or unaccredited investors, but, they also includes wealthy, angel or accredited individual investors. The goal is to provide them the deal structure that institutional investors in this space—venture capital (VC) and private equity (PE) firms—routinely get when they provide equity capital to companies.

The chart below shows that there are two pathways to improve access to capital for companies-the private sector or government. Government capital is available to a small proportions of companies (e.g., defense, energy, healthcare), usually as a grant or loan guarantee, not equity (i.e., investments where stock is issued). Government spurs the availability of equity capital via tax incentives and regulatory reform.

By and large, equity capital comes from the private sector, from those who meet the SEC's definition of an "accredited investor"(i.e. institutions and wealthy individuals) and everyone else (unaccredited or average/small investors). As a rule, only accredited investors may invest in a private company and anyone can invest in a public company. By meeting the requirements to offer stock to anyone, a company becomes "public."

The Fairshare Model is a market-based approach to the venture-capital market. To succeed, it requires stronger market forces—public investors who assert their power to influence the market.

The macro-economic benefit of the Fairshare Model?

Young, innovative companies are the engine of economic growth and job creation—it follows that improving their ability to raise venture capital should provide broad based social benefits in the form of economic growth, even after considering that venture-stage investing has a high risk of failure—investor loss. The model does not reduce the risk of failure for the public investors. It does, however, reduce the cost of failure because it of how it resolves the uncertainty associated with valuing uncertainty, future performance. Think of the casino game of roulette. The model does not change the odds that a single bet will pay off, rather, it reduces the cost of each chip. This allows the gambler to place bets on more numbers for the same money. More bets on start-ups should pay off, in a macro-economic sense.

This activity has a less obvious social benefit. Even when ventures fail, they contribute to a risk-taking, innovation-seeking culture. Such a culture is richer and more vibrant and productive in the long one than one that is timid and conventional. The national psyche is healthier when it is optimistic about possibilities and forgiving about shortfalls.

Another benefit of the Fairshare Model is that is a private sector approach to reduce income inequality; it does something without the need to achieve elusive political consensus. It does this by enabling employees to benefit from the wealth they create for investors. Put another way, we live in a time when the return on capital exceeds the return on labor, and, this dynamic is unlikely to change. The model addresses income inequality because it provides a vehicle for the providers of labor to participate in the return on capital generated by their labor.

The Fairshare Model rethinks capitalism, but it needs your interest and thousands of others to get off the ground.

Let's start the conversation.

Brief Question & Answer

The Fairshare Model is a Big Idea that is simple and intuitive in concept but it has a myriad of facets. So does a conventional capital structure, but few of us contemplate them because there has been no alternative to consider. The balance of this chapter briefly addresses questions that you, Dear Reader, may have before launching into the deep and occasionally meandering dive.

What is a public offering?

Stock in a public offering may be legally sold to anyone-including small investors. Such an offering is registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (e.g., S-1, SB-2 offering) or qualifies for an exemption from registration (e.g., Regulation A, SCOR offering).

A public offering has disclosure requirements; regulators seek to ensure that anything an investor ought to consider is disclosed. Private offerings are not subject to much in the way disclosure requirements; since the investors must be accredited, public policy presumes they are smart enough to perform prudent due diligence before they invest.

Interestingly, many people assume securities regulators ensure that public offerings meet a quality standard of sorts—that they make sure that only solid companies with plausible prospects can sell stock to the public. In truth, they enforce a disclosure standard. The presumption is that if a company clearly discloses sobering aspects of its business, investors will avoid it. A former SEC examiner told me "You can sell stock in a dead horse…so long as you disclose that it's dead!"

How expensive is a public offering?

The cost of a public offering varies based on the complexity of the disclosures, the amount of money raised and how it will be sold. Companies that raise capital via a Wall Street IPO often spend millions for underwriters and substantial legal, accounting and printing fees, plus the expense of a "road show"for management to pitch their deal to large investors.

The Internet can greatly reduce the cost of a public offering. The ability to reach investors directly enables an issuer to save as much as 13% in broker-dealer commissions and expenses. There is little or no printing or road show expense. And, a start-up will have simpler disclosure requirements because there is less to say. For such a company the cost of a direct public offering to raise up to $5 million might range from $75,000 to $200,000. Associated costs of being a public (i.e., legal, accounting, director & officer insurance, investor relations, etc.) can range from $300,000 to $800,000 per year; many variables affect this.

One thing is consistent, however, the cost and time it takes to find, engage and sell investors a new offering is the most significant challenge a company has. That's why issuers routinely hire broker-dealers; they have the names of and relationships with investors that issuers lack. They also provide comfort to investors in the form due diligence and other ways of bringing credibility to an offering. The biggest hurdle a company faces when it goes public without a broker-dealer is how to find, engage, and sell the offering to investors. The greatest hindrance these investors face may be gaining comfort with an offering, including performing due diligence.

The Fairshare Model can mitigate these problems. If an issuer adopts the model, it inherently provides comfort to investors. As the number of investors who like the model grows, issuers will have an instant affinity group to present their deal to. If broker-dealers are engaged, they should charge less because such an affinity group makes their job easier.

If start-ups close their offerings faster and investors have better terms, it's good for the economy; funded innovators help grow the economy and create jobs.

What is venture capital?

Venture capital is popularly construed to be a private investment by wealthy private investors or funds, something that is too risky for public investors.

I define it more broadly; it's an investment in a venture-stage company, be it via a private or public offering. A foundational concept of the Fairshare Model is that capital provided to a venture-stage company is "venture capital"whether it is supplied by accredited investors or from public investors.

It's legal to raise venture capital in a public offering. It just wasn't popular with investors—it was viewed as too risky. That mindset began to change in the 1980's. Since then, it's no longer odd to see a venture-stage company raise venture capital via an IPO.

Instead of saying "you're drawing a distinction where there is no difference", a professor of mine used to say "same girl, different dress". Lady Gaga is fun and offers an apt image but some readers may prefer "same guy, different suit".

What is a venture stage company?

Such a company has the following risk factors:

- Market for its products/services is new/uncertain

- Unproven business model

- Uncertain timeline to profitable operations

- Negative cash flow from operations; it requires new money from investors to sustain itself.

- Little or no sustainable competitive advantage

- Execution risk; team may not build value for investors

Many public companies list such risk factors in their offering documents and other regulatory, so, it's clear that unaccredited investors are already public venture capitalists!

So, one might ask, "what's all the fuss about equity crowdfunding?"

Is the Fairshare Model "crowdfunding"?

Not as you may understand it. That said, a company that adopts the Fairshare Model will almost certainly use an equity crowdfunding campaign because they are likely sell their shares directly to the public, in what's known as a direct public offering (or DPO). The alternative is to hire a securities broker-dealer (a/k/a investment bank) to sell the shares in an underwritten offering.

Equity crowdfunding is popularly considered an innovation in distribution, or, how shares are sold. Actually, companies with a DPO have used crowdfunding for years. The Fairshare Model is an innovative share structure (or substance); it can be distributed in any manner used by a conventional offering. These analogies make the distinction clearer.

- Where highly processed food is conventional, fresh and healthy food is an innovation in substance and local farmer's markets are an innovation in distribution.

- Netflix began as an innovator in how entertainment is distributed, not what the entertainment is. It now creates entertainment, it did not start off doing that.

- Tesla Motors innovates in substance (electric cars) and it also seeks to innovate in distribution by selling cars directly to customers, outside the dealer franchise model that dominates the auto industry.

An issuer with a conventional capital structure that has an offering via one of the new crowdfunding portals is an innovator in distribution, much like convenience stores were innovators in how consumers bought consumables like milk. But whether it's sold in a convenience store (or a grocery store), in substance, its milk. Similarly, whether stock is sold via a crowdfunding portal (or a securities broker dealer), a conventional deal structure is a conventional deal structure.

Chapter four discusses crowdfunding at length.

What is a Capital Structure?

A capital structure defines how ownership interests of a company are ordered. A corporation's incorporation document—it's constitution, if you will—is an explicit statements of these rights. The name of the document varies by where the corporation is formed or chartered; shareholders must approve changes to it. In many states, the document is called the "articles of incorporation"; sometimes, ownership rights are more fully described in an associated document, the corporate by-laws.

How ownership interests are ordered depends on those who craft it. A complex capital structure enables a company to offer special rights to a group or class of investors. Ultimately, the structure reflects the desire of existing shareholders, tempered by what it takes to attract new investors.

What is a "class"of stock?

A way to distinguish shareholders who have different rights from others. The principal rights at issue relate to voting, dividends, price protection (a/k/a anti-dilution) and liquidation preferences (i.e., the right to be paid before other shareholders).

When a company has one type of stock, it's called common stock. When certain shareholders have rights that others don't, they are un-common…their distinctive class is usually called preferred, but some companies use a separate class of common.

When there is multiple classes of stock they may vary in seniority or preference; as a rule, all members of a class must be treated alike. Think of it as a ship; the quality of passage varies based on whether one is in first class, second class, etc.

"Investor Stock", "Performance Stock"…what are these names?

The names are used to aid comprehension. Investors get tradable stock for money, the Investor Stock. Employees get Performance Stock for future performance. Performance Stock converts to Investor Stock based on the performance of the company.

A company that adopts the Fairshare Model is likely to refer to its common stock as "Investor Stock"and a class of preferred stock for its "Performance Stock". Alternatively, it could have two classes of common stock (e.g., Class A and Class B).

What is a conventional capital structure?

In their book Freakonomics, Stephen Dubner and Steven Levitt write that famed economist John Kenneth Galbraith coined the term "conventional wisdom"to describe a convenient and comfortable point of view that is often false.

In this book, I alternately refer to conventional wisdom about how to organize the ownership interests in a corporation as a conventional capital structure or conventional model, and, the terms of the sale of stock using such a structure as a conventional deal. It is the nemesis of the Fairshare Model, which is decidedly unconventional.

Conventional capital structures come in a variety of shapes and flavors but they share two common characteristics;

1. A value for future performance must be set when a company issues new stock, and

2. Where the capital structure is complex, its purpose is to favor pre-IPO shareholders over public shareholders.

In its simplest form, a conventional capital structure is comprised on a single class of stock—called "common". All shares have the same rights. This can be the case whether the company is private or public. The Fairshare Model deviates from this—it creates complexity—in order to avoid the valuation problem for public investors; that's unconventional.

As discussed below, public companies add complexity to benefit certain pre-IPO shareholders and private companies add complexity to benefit professional investors. Never is the complexity created to benefit public investors; that's conventional.

Conventional capital structures in public companies

Generally, public companies have a single class of common stock. Those that have more provide some owners with special rights, typically around voting. A company could have multiple classes of common where each class has the same voting power (i.e., think "separate but equal"). However, multiple or dual-class common is usually established to give super voting rights or dividends to some shareholders (i.e., "separate and unequal").

When Ford Motor Company went public in 1956, Henry Ford and other shareholders wanted to create wealth for themselves but also wanted to maintain control of the company. They accomplished this by adopting a dual-class common stock structure. A Class A common stock was sold to the public and a Class B super-voting common stock that was entitled to special dividend income was retained by the insiders. In 2010, the holders of the Class B stock hold 2% of all the Ford shares but control 40% of the votes. [14] When it went public, Ford was well established as a profitable and growing company; there was no question about its ability to perform in the future.

When it went public in 2004, Google was an unprofitable challenger to dominant (and also unprofitable) search companies like Yahoo, so, there was question about its ability to perform in the future. Like Ford, Google adopted a dual class structure. It sold Class A stock to the public that has one vote per share while its pre-IPO shareholders got a Class B common stock that has 10 votes per share. The practice became more popular after Google did it—it was adopted by LinkedIn, Groupon, Yelp, Zynga and Facebook. Ever the innovator, Google, created Class C common shares it created in 2014 have no voting rights whatsoever! I call it "silent partner stock"and it demonstrates that a corporation has great flexibility in setting its capital structure. By the way, as of March 2014, its Google's founders control more than 55% of the vote despite owning only 15% of the total shares. [15]

Public companies may have one or class of preferred stock, which is senior to common. It's not often used, but when it is, it's usually to provide the shareholder with a dividend that common shareholders don't get. Public technology companies rarely use preferred stock.

Conventional capital structures in private companies

Private companies rarely have more than one class of common stock and, often, they have preferred stock. In fact, those with professional investors—VC and PE funds—always have preferred stock, a series for each round of financing. So, a company that has raised three rounds of capital from VCs can be counted on to have three series of preferred stock (designated Series A, B and C, or, Series 1, 2 and 3).

Professional investors carefully craft the terms of the preferred stock. The rights and privileges determine which shareholders get what under scenarios that span from liquidation, continued operation, to acquisition or public offering. The terms are complex and arcane; the results may be counterintuitive. For example, early investors may be entitled to more of any proceeds than later investors who invest larger sums due to "superior liquidation preferences"or "cumulative dividend rights". "Anti-dilution"provisions provide price protection against having bought in at too high of a valuation; if the valuation in a subsequent round of investment does not surpass a target, investors with such rights get additional shares for their original investment (i.e., a retroactive reduction in price per share).

When a company with such investors is about to be acquired or have an IPO, the number of preferred shares are tallied up and convert into the common stock that is bought by the acquirer or registered to trade in the market.

Is a stock option that vests based on performance the equivalent of Performance Stock?

No. A stock option does not have voting rights, Performance Stock does.

How is performance defined and measured?

This is a large question for which there is no short or uniform answer. If there is significant interest in the Fairshare Model, there will be lots of discussion around how to answer this.

The Fairshare Model is not an off-the-rack, one-size-fits-all solution. Each company and its investors will decide how to answer this question based on its industry, stage of development, strategy, culture and employees. For example, a life science company will define performance differently than a company that makes software, food or a non-regulated device. The form adopted will also reflect the personalities of the company's management and their investors. The differences may be reflect sensibilities that differ by geography; Silicon Valley California vs. Silicon Whatever [16] or the industrial heartland.

Who gets the Performance Stock?

Same answer as provided for the last question.

Has the Fairshare Model (or anything like it) been used before?

Not in a way that benefits average investors. However, when professional investors negotiate the terms of an investment, they apply concepts that are in the Fairshare Model. When investors like a company, their foremost concern is that they buy in at too high a valuation. Accordingly, they require price protection; terms that reduce the price they pay if the company fails to perform as expected.

Acquirers, companies that purchase other companies, have two ways to apply this concept. An earn-out clause allows a seller to get a higher price if the company performs well after it is acquired. A claw-back clause enables a buyer to recover some of the price paid at acquisition if the seller's company does not perform well enough.

So, the underlying idea of the Fairshare Model—price protection for investors—is well accepted. What makes it novel, even radical, is that it extends it to average investors.

Warehouse clubs like Costco disrupted the market for consumer goods by offering warehouse pricing to the mass market. The Fairshare Model provides a deal structure that encourages venture stage companies to offer their stock to average investors at what might be considered the wholesale price (what professional investors would pay).

Do securities laws have to change to make the Fairshare Model legal?

No laws need to change. It would be helpful, though, were issuers required to disclose and discuss the valuation that they give themselves, given the terms of their offering. This would help investors become valuation-savvy. It would also encourage issuers to compete for public investors by offering lower valuations and stronger investor protections.

Title III of the JOBS Act has a requirement that issuers disclose and discuss their valuation. But that section of the rules has not been implemented yet, so one can't assess its effectiveness. In Section III, I have much more to say about importance of valuation disclosure and how you, Dear Reader, can express your support for it.

When investors are well-informed, companies that adopt the Fairshare Model will have a competitive advantage in attracting investor capital. The model also promises to provide a company with a competitive advantage in attracting and managing human capital.

What is the attraction of the Fairshare Model for public investors?

Public investors can invest at a low valuation—closer to what a VC would get than to the high valuation normally associated with a public offering. They know that the employees of the company they invest in have high incentive to deliver the performance that will convert Performance Stock.

The stock is far less susceptible to nefarious "pump and dump"schemes by unethical promoters and stock dealers. This occurs when a stock, usually a thinly traded one (i.e., penny stock or one that trades on the pink sheets), is hyped by parties who have people who have stock to sell. The owners of Investor Stock paid money for their stock or they earned it via performance—they are more likely to hold shares for the long-term than a flip oriented shareholder.

Public venture capital investors who are accredited will like the ability to liquid their position, if the company trades on an exchange.

What kinds of companies might want to use the Fairshare Model?

Companies that have raised a round or two of funding from angel investors and now need $5 million or more in venture capital. For such a company, the Fairshare Model is an alternative to a round from a venture capital fund. There is no limit on the amount of capital that could be raised.

Companies who adopt the model will be confident in their ability to perform. In addition, they will see competitive advantage in being able to use Performance Stock to attract and motivate employees. Their management will be willing to offer public investors a low valuation in exchange for the opportunity to earn a high percentage of the Investor Stock. A company that sees a benefit to using equity crowdfunding to market its product/service will certainly be drawn to the Fairshare Model.

Beyond that, there will be companies that have poor access to professional venture capital, perhaps because of where they are located or their industry, or, they don't like the deals that are offered.

Chapter five describes four categories of companies likely to adopt the Fairshare Model. One category is a company that wishes to be acquired—at a healthy premium—once they complete product development and demonstrate market acceptance for their technology. Two companies recently demonstrated success with such a strategy. In 2012, SmartThings raised $1.2 million in rewards-based crowdfunding. It then raised $16 million from VCs. In 2014, Samsung acquired the company for $200 million. A similar course was charted by Oculus VR. In 2012, it raised $2.4 million in rewards and contribution based crowdfunding, then raised $91 million in two VC rounds before being acquired by Facebook for $2 billion in 2014.

Undoubtedly, there will be companies that believe they can parlay an early IPO into a handsome gain for investors in such a manner. For them, the appeal of the Fairshare Model over a VC round will be that insiders can have more control, and the opportunity to own a greater share of the wealth, than they would have if VCs were the backers. In addition, they will be able to broadly distribute their equity among early supporters.

What is the attraction of the Fairshare Model for a company's private investors?

Their company may be able to attract the next round of capital on better terms than a VC would offer. If the company struggles after a VC round, odds are that the angel investor's position will be squeezed. Plus, their company may perform even better with the Performance Stock program!

Of course, there is the attraction of being able to sell off shares in the secondary market. If the stock does well, they can sell off enough to recovery their invested principal and hold the remaining shares as an upside.

What is the bargain between a Fairshare Model company and its investors?

If the company performs, investors will be diluted on a percentage basis —their slice of the ownership pie will be reduced. If the performance is good, they will experience heavy dilution.

On an economic basis, however, if the performance translates into a higher valuation, investors should not suffer dilution. In other words, investors have a smaller piece of a larger pie and the value of their piece is higher than their investment.

VCs like to say "I'd rather own a small slice of a big pie than a large slice of a small pie". Same principle.

What is the bargain between the company and its workforce?

In addition to the typical forms of compensation--salary, benefits, bonuses and stock options on its Investor Stock-- employees have an interest in its Performance Stock pool. As the team performs well enough to meet the conversion criteria, employees have another way to earn stock that they can sell (or hold).

How does a stock option compare to an interest in Performance Stock?

Though conceptually similar, Performance Stock is an issued security (and it is senior to Investor Stock) and a stock option is not, it's a derivative instrument. Performance Stock is senior to Investor Stock even though it can't ever trade; it has the potential to convert to the junior, tradable Investor Stock. Performance Stock votes and does not expire. A stock option does not vote and has a limited life, a term.

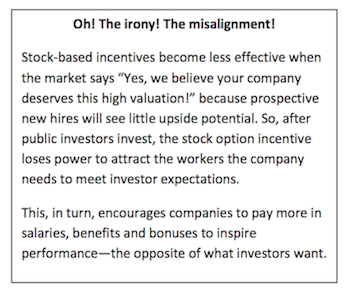

Employee stock options have made many people millionaires in recent decades. A company that uses the Fairshare Model can offer options on its Investor Stock, just like a company with a conventional mode does. But, job candidates are likely to see greater upside to options from a Fairshare Model company because the grant price will be based on a lower share price.

This is a downside of a conventional capital structure. Option grants tied to an excessively high valuation have little appeal to new employees; they sense it may require an Act of God to keep it at its present value, let alone increase it!

If a private company is the competition for the job candidate, more information is needed to determine who has the edge. If it is VC backed, that company has allure in the eyes of candidates but it diminishes as it approaches an IPO because option grants are smaller in terms of shares and higher priced. This seeds disharmony in the workforce. Workers with comparable jobs may have great variation in the upside of their stock incentive that reflects the valuation when they joined and their negotiation--neither of which correlates with performance, by the way.

The "secret sauce"of the Fairshare Model is its potential to help companies that use it to out-compete other companies for employees, and, to elicit coordinated, cooperative effort to achieve the goals that investors have. A company that adopts the model can offer an employee stock options that may have more potential for gain, but they can offer something else that other companies cannot--an interest in its Performance Stock. The share's value is equivalent to founder's stock—cheap. That's because its only value is the ability to vote and its potential to convert based on performance. The company that uses the Fairshare Model can say to employees "If we, as a team, deliver the performance that our Investor Stockholders expect, you will get shares of Investor Stock". Beyond the financial incentive, there is the highly powerful appeal of joining a team of people who work with common purpose.

What challenges does the Fairshare Model face?

Broadly, there are three phases of challenge.

The initial one is to establish that there are many investors who would seriously look at investing in a company that adopts Fairshare Model. If you like it, know that BEFORE companies think about how to make the Fairshare Model work for them…

….A LOT of you need to make a little bit of noise….

…like, like, well…

…like the tiny residents of Whoville in Dr. Seuss's children's book Horton Hears a Who! [17]

With each of your small voices you need to create buzz. You can cause others to take note and join in.

People who like the Fairshare Model must combine their small voices and shout….

The second challenge will be to debug and shakedown the Fairshare Model. This will largely be done by experienced entrepreneurs, attorneys, accountants, angel investors and other professionals in investment and finance who advise companies of capital formation strategies. However, anyone can contribute. The big questions will be what I call the "Ponderables", some which are listed below.

- How might performance be defined?

- Who should define performance?

- How might it be measured?

- Who should measure it?

- How should rewards of performance be allocated?

- Who should administer the rewards of performance?

- What are the tax and accounting implications of the Fairshare Model?

The best answers to these questions will emerge from discussion, debate and experience with its innovative structure. Finding them will present beguiling questions about how to square human nature and the Fairshare Model.

Our founding fathers engaged similar discussion as the structure of government was debated. These pathfinders sought an alternative to dynastic, feudal form of government. Their first product was the Articles of Confederation, which proved to have serious flaws—its strong state—model inhibited the ability of the states to function in a united form. The Federalist Papers, a series of pamphlets written by James Madison, Thomas Jefferson and John Jay fed public discourse on how to redefine the structure. In 1788, twelve years after the American Revolution, James Madison described the central challenge of defining a stronger central or federal government in this way.

But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature?

If men were angels, no government would be necessary.

If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.

In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself. [18]

Therefore, the third challenge for the Fairshare Model will be time and experience.

The product of the founder's deliberations was the U.S. Constitution. Yet, that didn't get it right, as witnessed by the number of times it was amended— ten times before it was ratified and more than thirty times since. One measure of how difficult is for people to come up with a set of durable rules that fits their needs and times is that there have been more than 11,500 amendments proposed to the U.S. Constitution since it was ratified by the Congress.

Of course, that does not cover the challenge of applying a rule. Again, the U.S. Constitution is instructive. Over the years, there has been conflict over how to apply its meaning—as a strict constructionist or through interpretation of what the founders might intend, if they were presented with a contemporary situation.

For the Fairshare Model to gain widespread acceptance, pacts that are comparable to those between the government and the governed must be formed between investors (the providers of capital) and the providers of labor (management…and workers). It must make money for both—much more money than a conventional model.

Sustaining goodwill among these groups is the central challenge for companies that adopt the Fairshare Model. It will be harder for a large company, where the constituencies are far more diverse than for a start-up, where common interests are easy to identify. Early implementations of the model may reveal flaws it its approach to "government". If so, hopefully, fixes will be adopted in a manner similar to how the flaws of the Articles of Confederation were corrected by the Constitution, which was again repeatedly amended.

Again, there will be variations on the Fairshare Model, just as there are variations on a conventional capital structure and variation in how capitalism and democracy are practiced. Ultimately, it will present an ongoing laboratory to study human behavior and variations in organizational behavior.

Fairshare Model Principles

The five principles that guide the Fairshare Model are:

1. Wealth Creation, Not Wealth Transfer : Insiders don't become wealthy just because public investors supply the venture capital, rather, they become wealthy by delivering performance.

2. Valuation : Public investors get a deal that is similar to what pre-IPO investors get in a conventional IPO.

3. Share Distribution : The issuer allows a broad number of investors to buy shares at the IPO price.

4. Control : Voting control is equitably shared between investors and insiders.

5. Incentive : If they deliver the requisite performance, insiders can acquire most of the tradable shares.

Onward

The next chapter will discuss a conventional capital structure-the status quo-which has strengths as well as weaknesses. The weaknesses become apparent when applying it venture stage companies.

[12] Delloite, "Crowdfunding portals bring in the bucks" http://www.deloitte.com/Predictions2013 . "Venture capital, which gets the most media attention, is actually the smallest category. Expected changes in securities regulation could make it possible for companies to raise money via a crowdfunding portal, with contributors receiving an equity stake in the company. This category is the wild card. It could raise more than a billion dollars if the rules change, but less than $50 million if they don't."

[13] I use "employees"broadly; it includes founders, members of the board of directors, management, non-management employees as well as consultants.

[14] http://www.forbes.com/sites/joannmuller/2010/12/02/ford-familys-stake-is-smaller-but-theyre-richer-and-remain-firmly-in-control/2/

[15] Financial Times, 4/2/14, "Google founders look to cement control with novel share split", by Richard Waters. http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/5ba9a078-b9f2-11e3-a3ef-00144feabdc0.html#axzz37fGKPluL

[16] Under "List of places with 'Silicon' names"Wikipedia identifies more than two dozen monikers in the U.S. with a "Silicon"reference (Silicon Alley, Silicon Hills, etc.) It's popular in other parts of the world as well.

[17] The book tells the story of Horton the Elephant who hears a small speck of dust talking to him. He discovers that it is actually a tiny planet , home to a microscopic community called Whoville , where the Whos reside. The Mayor of Whoville asks Horton (who, though he cannot see them, can hear them with his large ears) to protect them from harm, which Horton agrees to do, because "even though you can't see or hear them at all, a person's a person, no matter how small."Other animals in the jungle ridicule for believing that there is anyone on that speck of dust because they are unable to see or hear them. The animals cage Horton and threaten to drop him in boiling oil if he does not drop the speck of dust into it. Horton tells the Whos that they need to make themselves heard to the other animals. The Whos accomplish this by ensuring that all members of their society play their part in creating enough noise to be heard by the other jungle folks. Convinced of the Whos' existence, Horton's neighbors vow to help him protect the tiny community.

[18] Number #51 of the Federalist Papers

Karl M. Sjogren *

Contact Karl Sjogren is based in Oakland, CA and can be contacted via email or telephone:

Karl@FairshareModel.com

Phone: (510) 682-8093

The Fairshare Model Website

A native of the Midwest, Karl Sjogren spent most of his adult life in the San Francisco Bay area as a consulting CFO for companies in transition—often in a start-up or turnaround phase. Between 1997 and 2001, Karl was CEO and co-founder of Fairshare, Inc, a frontrunner for the concept of equity crowdfunding. Before it went under in the wake of the dotcom and telecom busts, Fairshare had 16,000 opt-in members. Given the rising interest in equity crowdfunding and changes in securities regulation ushered in by the JOBS Act, Karl decided to write a book about the capital structure that Fairshare sought to promote….”The Fairshare Model”. He hopes to have his book out in Spring 2015. Meanwhile, he is posting chapters on his website www.fairsharemodel.com to crowdvet the material.

Material in this work is for general educational purposes only, and should not be construed as legal advice or legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances, and reflects personal views of the authors and not necessarily those of their firm or any of its clients. For legal advice, please consult your personal lawyer or other appropriate professional. Reproduced with permission from Karl M. Sjogren. This work reflects the law at the time of writing.