The FairShare Model: Chapter Thirteen

Karl M. Sjogren

2015-07-02

Chapter 13: Evaluating Valuation

By Karl M. Sjogren *

Send comments to karl@fairsharemodel.com

Preview

- Foreword

- It's in the Eye of the Beholder

- The Next Guy Theory tells you all you need to know

- Is there an intrinsic value?

- How Valuation Experts Approach Valuation

- Weaknesses of valuation expert approaches

- Rules of Thumb

- Non-Quantifiable Factors-the Power of Love, Reputation and Charisma

- Quantifiable factors for evaluating valuation

- How VCs Evaluate a Valuation

- How Angel Investors Evaluate a Valuation

- How Private Equity Investors Evaluate a Valuation

- Evaluating the Valuation of a Company That Uses the Fairshare Model

- Closing thoughts

- /Onward

Foreword

How does one assess a valuation? Say that you know a company gives itself a $10 million valuation, can one say, it's a bargain, because it really should be an $11 million company? Or, that it is a wee bit over the right price of $9.5 million? What would a savvy investor value it at? If there is no performance-it is worth anything? This chapter provides an overview of the approaches to assess a valuation

It's in the Eye of the Beholder

Value, like art, is a concept, especially if the object has little utility. It is more in the eye of the beholder than an objective measure. In addressing the difference between price and value, Peter Bernstein, author of Capital Ideas, put it the following way [bold added for emphasis]: [13]

From Adam Smith, the eighteenth century author of The Wealth of Nations, all the great economists have wrestled with this problem in one form or another; it plays a central role in Karl Marx's model of capitalism.

Economists agree that "value" refers to something that lies behind, or beneath, the prices observed in the marketplace; prices gyrate around "true value". But what is "true value"?

The question is not unlike the exchange between three baseball umpires trying to describe how they distinguish between a ball and a strike. "I call them as I see them", said the first. ""I call them as they are", replied the second. "They ain't nothing till I call them", declared the third.

Is value a subjective quantity? Or is it a quality that cannot be measured except by some objective standard? Or does value emerge only when a transaction takes place in which buyers and sellers agree on a price?

The reason stock prices jump around so much, and the reason stocks are considered such a risky investment, is that there is nothing clear-cut about their value. Is GM worth $50 a share because the accountants, in their wisdom, add up GM's assets, deduct its liabilities and find that the difference is $50? Or is worth only $40 because a security analyst applying the [Discounted Cash Flow] model finds $40 to be the discounted present value of GM's future cash flows? Or is it worth perhaps $60 because there is a rumor that the hot mutual fund manager or the latest takeover artist is buying it, and everyone knows that what they buy is bound to go higher?

The most pessimistic and disturbing, and the most amusing answer to these questions came from [economist John Maynard] Keynes, who was no mean speculator in his own right. Published in 1936, Keynes' sarcastic indictment of the stock market appears in a chapter in the General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, in which he uses the phrase "prospective yield" to refer to the intrinsic value of an asset:

"It is not sensible to pay 25 for an investment of which you believe the prospective yield to justify a value of 30, if you also believe that the market will value it at 20 three months hence…

Human nature desires quick results, there is a particular zest in making money quickly, and remoter gains are discounted by the average man at a very high rate.

It is, so to speak, a game of Snap, of Old Maid, of Musical Chairs-a pastime in which he is the victor who says Snap neither too soon or too late, who passes the Old Maid [card] to his neighbor before the game is over, who secures a chair for himself when the music stops."

The Next Guy Theory tells you all you need to know

Bernstein's perspective is instructive for venture-stage companies. Valuation is a pretty straight forward measure to calculate, but evaluating whether one is high, low or just right is a highly subjective matter. Keynes zeroed in on the importance of the "prospective yield" in determining the "intrinsic value" of a stock. Essentially, this is the Next Guy Theory of pricing for an investment, described in chapter three as:

For an investment, the price is no more than what the buyer believes the Next Guy will pay, less a discount.

No matter how you evaluate a valuation, it boils down to an effort to figure out what the Next Guy might pay. It may be driven by mathematical exercise but ultimately it is a bet on human behavior.

To appreciate this, let's first examine the quantifiable issues that effect how a valuation is evaluated. Then, we'll look at some of the non-quantifiable, emotional ones

Is there an intrinsic value?

Finding a way to define and assess an intrinsic value to a company has long been the Holy Grail of financial market theorists. If one could discern it, one would know which stocks to sell or to avoid buying for the reason that they were overvalued. If a stock was selling below its intrinsic value, it might be promising to buy it. If investors knew a company's intrinsic value, they would be less susceptible to FOMO-Fear Of Missing Out-when valuations rose on a speculative basis.

Peter Bernstein wrote that "the most rigorous, and also the most influential, method for determining intrinsic value was published in 1938 by John Burr Williams," in his dissertation for a doctoral degree in economics. [14] Bernstein adds that Williams' "solution continues to be applied to almost all valuation problems…it provides the only formal method for determining what a price/earnings ratio or a dividend yield should be. Comparing that ratio or yield gives an indication of whether the asset is cheap or expensive."

Williams developed a theory of intrinsic value that "rests on the proposition that an asset is worth only what its owner can get out of it" which he defines as the sum of its future cash flows discounted to its present value for the time value of money. By extension, the present value of a company, its intrinsic value from an operating point of view, is today's value of the cash flows it generates in the future. [15] An operating point of view assumes the business continues to operate; a liquidation perspective considers value from the point of view of a buyer of the entire company or its key assets.

Money expected in the future is never worth as much as money on hand today because of the time value of money-which is the interest rate that one could earn if the money were available now, plus, the risk that the money will not actually be there when expected. Bernstein continues "The process of giving future payments a haircut to allow for uncertainty and the passage of time is known as discounting, and investors call this valuation technique the Dividend Discount Model [or Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) model]. The model is applicable to any kind of investment that is designed to produce cash flows to its owner in the future. [16] Few investors perform the elaborate calculations required by the model. Yet, no other formula for determining intrinsic value makes sense."

In the case of the DCF valuation model, the strange thing is that one must forecast cash flows to infinity in order for the formula to work. So, for example, if one wants to forecast the value of a company five years out, one must project cash flows over the next five years, of course, but also what it will be annually, starting in year six, in perpetuity. The value that runs from, in this example, year six to infinity is called the "terminal value." It is clearly an act of necessary make-believe. Chapter nine has Maynard Webb's observation that one third of the Fortune 500 companies as of 1970 no longer exist. Product life cycles are rapid and dominance in one phase is no assurance of continued success-(e.g., Microsoft, Nokia, Toys R Us, Sun Microsystems, AOL Time Warner, etc.). As absurd as the terminal value assumption is, it's a necessary fiction for the DCF calculation to work.

Therefore, "the most rigorous, and also the most influential, method for determining intrinsic value" for a company that makes a mobile software application must forecast cash returns far beyond any credible assumption about the life cycle of the platforms that it plans to operate on. An innovative food product or a new technical device is expected to be generating returns 10, 20 and 40 years later. Here, theory clearly does not reflect experience.

Mathematicians who theorized about intrinsic value of financial assets in markets recognized this problem, which was acute in the case of "growth stocks"-companies whose earnings and dividend streams were expected to rise continuously into the future. In 1957, David Durand, a MIT professor of economics, wrote that:

Growth stocks…seem to represent the ultimate in difficulty of evaluation. The very fact that [this extrapolation problem] has not yielded a unique and generally acceptable solution to more than 200 years of attack by some of the world's greatest intellects suggests, indeed, that the growth-stock problem offers no great hope of a satisfactory solution.

How Valuation Experts Approach Valuation

Despite the challenges, the question, "what is a company worth?" often demands an answer. Most acutely by parties to a negotiation about price. Less urgently, by those who account for an acquisition in the months and years that follow the event.

Interestingly, those who negotiate the price often don't rely on valuation experts. It may sound curious because, after all, isn't that what valuation experts do…establish the price? The answer is "no." Valuation experts are not deal makers; they rarely establish price. Rather, after the deal is done, they assess how to account for the negotiated price. In other words, if they find that the price of a company, like any other asset, was higher than what it is worth, it results in a write-down in the asset's value-the recording of an expense.

So, how do valuation experts estimate how much a company is worth? They evaluate it from three perspectives-the income approach, the asset approach and the market approach.

The income approach provides the highest measure of enterprise value for a start-up because they rarely have valuable assets and their market value reflects expected income. To apply it, a discounted cash flow calculation is applied to a company's multi-year income projections. [17] Models vary sophistication but all rely on assumptions that require subjective judgement and are vulnerable to computational and logic errors.

Once projections are made, a discount rate is selected. The first step is to select a risk-free interest rate for the time value of money (i.e., rate on a U.S. Treasury note). The second step requires judgment; quantification of risk that the projections will not be met, and, the risk of converting the income to cash (i.e., liquidity risk, which relevant when earnings are in a foreign currency). The higher the risk, the higher the risk premium. The risk-free rate and the risk premium are added together to get a discount rate.

Discount rate = Risk-free interest rate + Risk Premium rate

So, if the risk-free interest rate is 3% and the risk premium is 14%, the discount rate is 17%. This is the "cost of capital", the rate of return required to attract risk-aware investors. There are tables that express a discount rate into percentage factors. These are applied to each period's earnings. The sum is the present value of the projected earnings

The asset approach to valuation considers what another party might pay for the assets or what it would cost to replace them. This approach is more likely to be used when a business is mature-it is rarely used to value a new company, which derives its value from its potential income.

The market value approach looks at the valuation of comparable companies. Interestingly, in a DCF calculation, value comes from income, but market value may be driven by revenue. The logic being that profits will follow or that revenue makes it more attractive as an acquisition.

Once valuation ranges using the income, asset and market approaches are in hand, a valuation expert will evaluate how to weigh them.

Weaknesses of valuation expert approaches

The combination of these three different approaches is intellectually impressive. Even so, the process does not consistently deliver practical value. If it did, valuation experts would be heavily relied upon by those who negotiate deals and established companies would not struggle to understand their value.

A fundamental problem exists when applying valuation methodologies to a start-up; such company is outside the "relevant range" of these techniques. That means an assumption about an activity loses relevance when it actual activity is higher or lower than expected. For example, costs considered to be fixed will not remain the same when volume is above or below the relevant range for the assumption.

Similarly, the logic used to measure value for an established firm may not be relevant for a startup, which has risks and opportunities that are not easy to assess. A startup that relies on innovative technology or a disruptive business model will have few comparable companies. Think of it this way, the strength of a chain is no greater than its weakest link-and when applied to startups, valuation methodologies have weak links.

The logic of the income approach is not its weakness, our inability to quantify risk and opportunity is. Another weakness of it is that start-ups are difficult to reliably forecast more than a year or two ahead. And the projections are the basis for all that follows-if they are unreliable, the discount rate doesn't matter. No matter how well constructed, a house will have flaws if it rests on a poor foundation. Another problem is that key assumptions often rely on subjective judgment that can be altered to deliver the results desired. Thus, the income approach can resemble a session with an Ouija board. [18]

What about the market approach? To speak to that, one must refer to valuation as price, not worth (income approach). Valuations often have a bipolar quality; they can climb and fall dramatically, out of proportion to what seems to be going on. This is apparent in the secondary market, where stock traders have a rule of thumb seemingly designed to feed volatility-"Buy on the rumor, sell on the news." It happens in the private market in a more dramatic, "sudden-death" fashion because valuation comes up when a company needs money. Thus if it's hot, the valuation will surge, if it's distressed, the valuation crumbles.

Valuation experts are no better than astute observers at explaining or forecasting price. They could not reasonably anticipate that the start-up ride sharing company Uber, for example, would be valued (priced) at $18 billion, as reported in mid-2014. [19] They would be unable to justify that unless comparable businesses, like Lyft, were similarly valued.

What is Lyft's valuation? Reportedly, $275 million in March 2013 [20] and $700 million a year later, when Uber set the $18 billion mark. [21] [Dear Reader, for fun, check what it is when you read this.]

Rules of Thumb

Another way to evaluate a valuation is to utilize rules of thumb such as a multiple of revenue, earnings or some other proxy for value like the number of customers. Use of a multiples of earnings before interest, depreciation (or amortization) and taxes (EBITDA for short) is popular, for instance. Some investors insist on paying no more than a multiple of the last round.

A multiple provides an approximation of value, albeit an arbitrary one, without a need to perform complex calculations. In the secondary market, an investor may have rule of thumb based on fundamental analysis, like the price/earnings ratio or on forms of technical analysis (i.e., pattern analysis, moving averages, etc.). Rules of thumb vary based on a company's industry, stage of development, geography and by investor. They are a convenient way to compare different companies.

Non-Quantifiable Factors-the Power of Love, Reputation and Charisma

More often than you might think, non-quantifiable factors affect how a valuation is evaluated. Caution can be thrown to the wind when the investor loves the idea and entrepreneurs. This happens to individual investors. But, as mentioned in chapter eleven, Garage Ventures' Bill Reichert reports that it happens to professional investors as well. Another such anecdote is provided by David Kilpatrick in his 2011 book The Facebook Effect. [Bold added for emphasis]

In venture capital deals…the investor usually forces the existing shareholders to dilute their ownership prior to the investment by adding a "pool" of shares that will remain unallocated, on the assumption that future employees will get some of their pay in stock options. The way it's calculated is complicated, but it has the effect of giving the VC more of the company and the entrepreneurs less. VCs typically insist that the existing shareholders of a company accept a pool of about 20 percent.

But [a Facebook co-founder] had prepared [CEO Mark] Zuckerberg for this gambit, and it was clear at dinner the night before how badly [Accel Partners' Jim] Breyer wanted to invest. So Zuckerberg refused the 20 percent dilution. The two agreed on a 10 percent option pool instead. In addition, Zuckerberg would only accept half of that being applied to existing shareholder's ownership. So some of the dilution applied to Accel's money as well. "Mark negotiated really hard," concedes Breyer.

They finally agreed on a deal that would value the company at slightly less than $98 million post-investment. Accel would invest about $12.7 million-a stunning sum for such a small company. It would own about 15 percent of the company. "I knew the price was way too high," Breyer says now, "but sometimes that's what it takes to do the deal." Breyer agreed to go on the board but asked if he could invest $1 million of his own money. The twenty-year-old and the VC shook hands. Zuckerberg left his office, and Breyer was elated. [22]

What causes an investor to fall in love with a prospective investment varies. Clearly, the business opportunity plays a critical role but so does the strength of the executive team.

For some, however, the team is more important than the business. The saying-"Bet on the jockey, not on the horse"-captures this sensibility." It's a way of stating that a smart, savvy CEO will make a great business achieve its potential and make a not-so-great business better than it might otherwise be. Interestingly, investors may value a company more highly than otherwise if a CEO has a reputation for delivering. A dream team makes investors more willing to accept a valuation because they make a good outcome more likely.

But the jockey effect can also lead to a hyped valuation. Imagine two companies with comparable prospects. One is led by a star, the other by someone less accomplished. The one with the hot CEO may fetch a higher valuation than can be explained by reduced risk; a valuation premium based on a halo or celebrity effect. Investors think "if so-and-so is on board, this is likely to be big!" From a valuation perspective, this is both understandable and curious. It is reasonable to favor a star CEO over an unproven one from a risk perspective, it is questionable whether a star makes the opportunity bigger.

Interestingly, a set of stars may not make a strong team; some may have trouble sublimating their egos to achieve goals that require collaboration. Also, past success doesn't assure future success, as many boards of directors have seen. That said, a CEO with a good reputation who puts the interests of others ahead of his or her own is the kind of jockey all investors want. Angel investor John Huston put it this way:

The one commonality of the successful exits we've had is simply this: the team, led by the CEO, was successful in convincing our due diligence team that they would be profoundly, personally embarrassed if they couldn't give us our money back with a nice multiple in 5 years. [23]

In his 2011 book, The Business of Venture Capital, Mahendra Ramsinghani describes qualitative factors that VCs consider when they evaluate a company and its valuation. He writes that Geoff Smart, co-author of the 2008 book, Who: The A Method for Hiring, sought to discover what kinds of CEOs make money for investors. To find out, Smart teamed up with Steven Kaplan, a professor of entrepreneurship and finance at the University of Chicago. Ramsinghani writes that [bold added for emphasis]:

[Smart and Kaplan] went on to conduct the largest study of CEO traits and financial performance. The results were compelling and controversial. Data from 313 interviews of [private equity]-backed CEOs were gathered and analyzed. Taking these assessments, the authors matched the CEO assessments with actual financial performance.

Smart points out that investors have a tendency to invest in CEOs who demonstrated openness to feedback, possess great listening skills, and treat people with respect. "I call them 'Lambs' because these CEOs tend to graze in circles, feeding on the feedback and direction of others," he says. And he concludes that investors love Lambs because they are easy to work with and were successful 57 percent of the time.

But Smart found that the desirable CEOs are the ones who move quickly, act aggressively, work hard, demonstrate persistence, and set high standards and hold people accountable to them. (He called them "Cheetahs" because they are fast and focused.) "Cheetahs in our study were successful 100 percent of the time. This is not a rounding error. Every single one of them created significant value for their investors," writes Geoff. He and his coauthor conclude that "emotional intelligence is important, but only when matched with the propensity to get things done."

Separately, Steve Kaplan's research leads to the same conclusion. In the study "Which CEO Characteristics and Abilities Matter?" the authors assess more than 30 individual characteristics, skills, and abilities. Surprisingly, the study showed that success was not linked to team-related skills and that such skills are overweighed in hiring decisions. Success mattered only with CEOs with execution-related skills. [24]

Ramsinghani addressed other reputational factors as well. He writes that integrity and honesty are fundamentally important qualities but hard to assess. With respect to experience, he references a study of serial entrepreneurs that concludes: [bold added for emphasis]

All things equal, a VC-backed entrepreneur who has taken a company public has a 30 percent chance of succeeding in his next venture. A failed entrepreneur is next in the pecking order with a 20 percent chance of success and a first-time entrepreneur has an 18 percent chance. Researchers assessed the cause of success and point out that successful entrepreneurs know how to launch companies at the right time-before the markets get crowded. [25]

This finding will be surprising to the many people-it was to me-because it is commonly thought that having an experienced, successful CEO (and other executives) on-board suggests less risk, if not more potential, thus a valuation premium. But the evidence Ramsinghani cites indicates that having a CEO with prior success increases the likelihood of success from roughly two in ten-the odds for CEOs that experienced and failed or those with no experience-to three in ten.

A Silicon Valley veteran told me that "VCs value formation of a 'team' as a proxy for execution"-a valuation premium. Again, this seems intuitive, after all, a sports team loaded with stars seems like it should be more valuable than one without a lustrous roster. But, what if the stars don't deliver? Does value flow from anticipation of performance or from the delivery of it? [26] Does valuation reflect hope or results? Variations of these questions can be formulated for other areas. Nonetheless, there is reason to believe that the valuation premium associated with prior success may be outsized. This will be one of many provocative points that comes up in discussions about the Fairshare Model.

Ramsinghani writes the following on the importance of team building, which further tempers the idea that a company should be valued more highly because of its team, before they deliver results.

"Do they understand their own limitations and weaknesses? Are they able to attract a team, and eventually, can they recruit their own CEO and replace themselves?" ask Lip-Bu Tan of Walden International.

These qualities are fundamental but rare-after all, human beings suffer from insecurities. If they attract team members who are highly accomplished, they may end up looking like dwarves. Or get sidelined! And very few can overcome this innate and primal urge-most gravitate toward looking smart in a land of dwarves as opposed to looking stupid among giants.

An investor needs to watch for traits where the founders or the core management team are able to attract star power. Most management teams will be replaced, either by choice or by sheer exhaustion in the travails of the start-up journey. Team building can make an investment opportunity stronger. A simple question to consider: Is this person honest and bold enough to replace him-or herself at the right time or even become redundant? [27]

Charisma is another intangible that can affect how a valuation is evaluated. An investor who is charmed by the leadership will like the company, maybe love it. This can lead to a valuation premium, if for no other reason that a high one is not questioned. However, charisma is that it is not closely associated with performance, as Susan Cain noted in her 2012 book Quiet.

The essence of the Harvard Business School education is that leaders have to act confidently and make decisions in the face of incomplete information. The teaching method plays with an age-old question: If you don't have all the facts-and often you won't-should you wait to act until you've collected as much data as possible? Or, by hesitating, do you risk losing others' trust and your own momentum?

The answer isn't obvious. If you speak firmly on the basis of bad information, you can lead your people into disaster. But if you exude uncertainty, then morale suffers, funders won't invest, and your organization can collapse. The HBS teaching method implicitly comes down on the side of certainty. The CEO may not know the best way forward, but she has to act anyway.

Yet even at HBS there are signs that something might be wrong with a leadership style that values quick and assertive answers over quiet, slow decision-making. Contrary to the school's model of vocal leadership, the ranks of effective CEO's turn out to be filled with introverts.

"Among the most effective leaders I have encountered and worked with in half a century," the management guru Peter Drucker has written, "some locked themselves into their office and others were ultra-gregarious. Some were quick and impulsive, while others studied the situation and took forever to come to a decision…. The one and only personality trait the effective ones I have encountered did have in common was something they did not have: They had little or no 'charisma' and little use either for the term or what it signifies."

Supporting Drucker's claim, Brigham Young University management professor Bradley Agle studied the CEOs of 128 major companies and found that those considered charismatic by their top executives had bigger salaries but not better corporate performance. [28]

It is easier, to be uncharismatic and effective when a business is established or in a turnaround situation. For a start-up, however, leadership charisma can play a more critical role. After all, like a magician or a ringmaster at a circus, the CEO is asking audiences to imagine possibilities, to have enough imagination to invest in, be a supplier to, or work for an enterprise that is doing something difficult when the prospect for reward is questionable.

If the opportunity is preternaturally compelling, CEO charisma may not be critical. But for many start-ups, a certain charm is necessary to cause investors to pay attention, to see the potential, to believe this team can achieve it and, finally, to actually write the check. It is one thing for charisma to encourage an investment, however, and something else for it to lead investors to accept a high valuation. It can be the difference between a healthy ego and narcissism: subtle but detectable. The thing about charisma is that you don't have to be competent to have it. Plus, it can lead investors, colleagues and the CEO him or herself to be overly confident.

There are an array of non-quantifiable factors that influence how investors evaluate a valuation--love, reputation and charisma are but a few.

Quantifiable factors for evaluating valuation

All investors rely on rules of thumb and non-quantifiable factors to evaluate a valuation because there isn't an intrinsic value to a venture stage company that can be reliably discerned. But sophisticated investors calculate what the company's pre-money valuation should be if they are to make the return they want on the investment. In other words, they don't calculate what the valuation actually is, they calculate the highest valuation they should pay to have a chance to make the money they want to make.

The calculation requires the investor to set a target rate of return for an investment with this expected risk, reward and length. It also requires prognostication of these variables:

- Expected value of the company at investor exit; and the

- Expected size and timing of future capital raises (i.e., how many more rounds of capital, and the share of the company they will buy).

The calculation works backwards. It takes the estimated exit value, deducts the expected dilution that will occur in future rounds to arrive at the future value of ownership now. Then, that value is discounted for investor's target rate of return. The result is an approximation of the maximum pre-money valuation the investor can accept and still expect to make its target return.

The details are too technical for this book. Besides, it's not relevant to public investors. They lack the opportunity to negotiate the pre-money valuation. Plus, they can sell before future ownership dilution occurs.

The take-away, however, is that sophisticated private investors often calculate the maximum valuation they can pay and still meet their goal.

How VCs Evaluate a Valuation

VCs routinely calculate the buy-in valuation they can accept using the approach above. They are also extraordinarily plugged into what is driving valuations. They hear what other VCs are doing. They know what potential acquirers and investment bankers are telling their portfolio companies. They may have board seats at companies that are in the space they invest in. They participate in networking events and hear from entrepreneurs who are at every point in the cycle. They have lots of eyes and ears on the ground.

So, they are expert assessors of valuation. But no one can know everything or reliably foretell the future. Therefore, VCs rely more on deal terms to protect them from overpaying than they do on calculation or negotiation. [See "Valuation is a Challenge for VC and PE investors" in chapter eleven.]

That is, to secure a position in a deal they want, a VC will accept a high valuation if they get price protection provisions (e.g., liquidation preference, dividends, etc.) and/or board control. These provisions are defensive in nature. They also secure offensive provisions-those that secure their right to invest more when a deal looks like a winner.

How Angel Investors Evaluate a Valuation

Like VCs, angel investors rely on rules of thumb and non-quantifiable factors to evaluate valuations. When they invest in businesses sectors that they know, or someone who they collaborate with knows, they have an informed opinion about what constitutes an attractive valuation. That's a way of saying that angel investors, especially those active in an angel investor group, rely more on their network to evaluate a valuation, whereas VCs rely on deal terms. Angel investors who are not well networked are disadvantaged in all aspects of the investment evaluation-due diligence and valuation.

David S. Rose is CEO of Gust, an online platform (www.gust.com) that is a terrific resource for angel investors and for entrepreneurs who want to pitch to them. In his 2014 book Angel Investing: The Gust Guide to Making Money & Having Fun Investing in Startups, he describes a variation of the calculation that was described on the prior page. He writes:

How much money you make from your angel investing is determined by four simple numbers: [29]

- The value of the company when you invest.

- The value of the company when you sell.

- The number of years between these two events, which, taken together, give you your rate of return.

- The rate of return, multiplied by the amount of money you invest, will determine your ultimate angel investing bottom line.

That first number, of course, is the pre-money valuation. Rose calls it "the single most important of the four simple numbers." He also refers to it as "the most confusing, debated and variable number in the world of angel investing."

In his book, Rose explains how to use the four numbers to estimate how much money an investor will make, including approaches that angel investors can take to evaluate the pre-money valuation of a private company. One thing he says about the process is relevant to public investors. He feels a 25% rate of return is roughly what angel investors should target, which is, as he point out is "a return that compares favorably to almost every other legal form of investment." [30] That may surprise readers accustomed to earning far less on their money but that rate reflects the risks that private venture-stage investors assume. Chief among them is the lack of liquidity. Once they invest, they are strapped in for the duration of the ride-no acquisition or IPO means little ability to convert their position into cash.

Beyond the expected difficulty of estimating the valuation of a company at investor exit and the time it will take to get there, angel investors face uncertainty about the percentage of ownership they will have in the company when the exit occurs. That's because the price protection that a VC secures comes at the expense of other shareholders.

Angel investors can correctly predict the exit value and time it takes to get there but vastly overestimate their return if they underestimate much capital, and what kind of capital, it takes to get there. For example, say that angel investors own 20% of a company that they expect will be valued at $30 million at exit, when they will own 10% or $3 million. They can be right about the exit value but very wrong about their stake; they could end up with 2% or $600,000…or even zero! How is this possible?

- An unplanned capital raise or a down round will trigger price protection provisions that the second round VC has, which dilutes the position of the first round angels.

- A VC may evoke a "pay-to-play" provision. This requires all investors to invest in a new round to preserve their ownership stake or lose much of their investment. In a pay-to-play scenario, investors who want to retain their ownership position ("play"), must invest more ("pay") in a new raise.

- A VC with a liquidation preference is entitled to recover it before other shareholders participate in the split of what remains. The preference is a multiple of the VC's investment.

- Professional investors may have the right to a dividend and/or management fee, which is compensation for the time the investment team spends overseeing their interests, but this is unlikely to be a significant issue unless the exit takes a lot longer than expected.

These glum possibilities don't necessarily affect how angel investors evaluate a valuation, though. After all, if they want to invest, they are excited and optimistic enough to believe things go as planned. Down rounds are never in a forecast. So, even though the projected exit value is spot on, changes in the timing of cash flows or shifts in the capital markets can drive a company to get the cash on terms that ultimately have adverse consequences for the angel investors.

Such possibilities shed light on why it can be so difficult for angel investors to evaluate "the single most important" number for an early round investment in a start-up.

Valuation Evaluation---As Seen On TV!

In 2009, as the U.S. worried about how get out of the Great Recession, the ABC television network debuted an entrepreneurial "reality show" called Shark Tank. [31] It's like a talent show, but instead singing or dancing for judges, contestants pitch their startup idea to a panel of five wealthy investors, who are called the "Sharks."

Novice entrepreneurs describe their business, demonstrate the product/service, then say "I offer X percent of my company for Y dollars." The amount seems to range from $30,000 to $300,000-a seed round size or early stage deal.

What follows is a bit of Q&A about the product/service, sales history/prospects and profit margin. The Sharks then critique the pitch and announce whether they are "out" of the deal or willing to entertain an offer. Competing bids occur.

Entrepreneurs always want the money and control. Counter offers are nearly always for a lower valuation and often require control. For example, an entrepreneur may offer 20 percent of the company for $300,000, a $1,200,000 pre-money valuation. [32] But a Shark is likely to counter with 51 percent (a $288,235 pre-money valuation) for the same money. [33] Sometimes, the counter has a royalty and/or loan component. Changes in deal terms can be hard for an entrepreneur to evaluate on camera, particularly if a royalty is involved and Sharks are saying "don't take that deal" or "you have an offer-decide now."

The show provides a reality-show like glimpse into the dynamics of valuation and deal structure. Watch some episodes and you'll see that the TV Sharks offer the lowest valuation they think they can get, but also look to secure at least one of the following:

- Ownership control-51 percent;

- Recovery of their investment, hence, a royalty;

- Leverage if the entrepreneur doesn't perform. Hence, a debt element, which can foreclose on the equity.

------------------------------------------

As an aside, royalty deals are generally a bad idea for a company, especially it margins are not high. They handicap the appeal of the company to new investors when more money needs to be raised.

Most angel investors and VCs see equity as mother's milk for venture stage companies and, so, don't require royalties.

How Private Equity Investors Evaluate a Valuation

Variation in the type of professional investors that engage in venture capital investing has grown since the 1990s. Once the province of venture capitalists, private equity firms and their variants (hedge funds, buyout firms, etc.) also engage in it. But they evaluate valuation in a differently way.

VCs invest in companies that are creating a business. Many of them are visionaries, like the entrepreneurs they back, in that they seek to create entirely new markets or to transform existing ones. They are like athletes who create their own momentum; weight lifters who lift from a standing start. Like gardeners who work with plants at a seed or sprout stage. Most significantly, they finance their companies with their own fund's money-if there is any debt, it is from equipment lessors.

PE firms invest in at a later stage, when there is an established business with assets that can be borrowed against. They are like gardeners who trim established plants, put them in a larger pot. Such investors are more opportunistic than visionary; they aren't interested in creating something new, they want to make something already in motion go forward, faster. It is hard to generalize beyond that because PE firms play in a bigger sandbox than VCs do-their stage of development spectrum is broader.

On the startup end of the spectrum, PE favors companies with existing products for which there is an attractive market. The gambit is that the company can accelerate its growth and improve its efficiency with the PE firm's capital, insight and connections. On the mature end of the spectrum, they invest in companies that could be worth a lot more with a makeover.

PE firms have the advantage over VCs when it comes to assessing a valuation. There is a historic trend to examine, much like an investor can see a public stock's trend. Their bet is that they can help it rise faster or fix what's wrong and then sell it at a profit. They have another advantage over VCs-because there is an existing business, they can structure their investment as debt or, even better, they can get others to lend the company money that can be used to buy the company.

Because cash flows are easier to project for an established business and repayment of debt plays a prominent role in building value, a PE firm will pay a lot of attention to a DCF analysis. As a result, their formula for success is a more precise version of the Next Guy theory. The three strategies that a PE firm can use to increase the value of their equity stake in a company are:

- Pay down the debt used to acquire the company by selling off assets (i.e., facilities or lines of business);

- Increase the earnings multiplier by re-positioning the business to focus on high growth and/or more lucrative markets; and

- Grow the income by increasing revenue and reducing expenses (i.e., cost reductions, drop low margin products, consolidate facilities, etc.).

How these strategies can pay off is presented on the next page. [34]

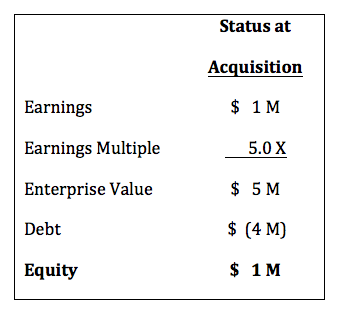

The table to the right shows a company with income of $1 million dollars that a PE investor acquires for $5 million-so, it is valued at a 5X earnings multiple.

To finance the purchase, the PE fund found a lender to lend the company $4 million, based on its assets, income and the PE investor's involvement. As a result, the PE investor makes a $5 million investment using just $1 million of its own money. The company's selling shareholders are paid $5 million, but $4 million of it came from money that the company borrowed, not the PE firm.

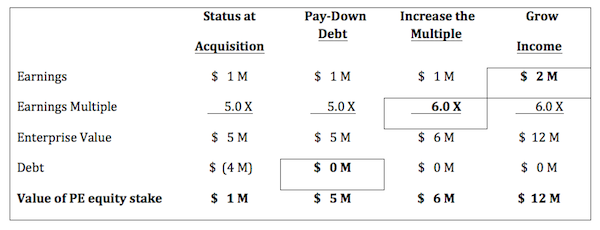

The next table adds three columns to the one above, one for each way a PE investor will try to increase the value of its equity stake before it has an exit (i.e., an IPO or sale to another party).

Let's walk through each of them, assuming they occur in succession:

- The "Pay-Down Debt" column reflects the sale of assets that are not critical to the company's new strategy. The proceeds are used to retire the $4 million debt. As a result, the value of the PE firm's equity stake rises from $1 million to $5 million. The company's value is unaffected, as it is function of earnings…the amount and the multiple.

- The "Increase the Multiple" column shows the effect of increasing the earnings multiple, here, from 5X to 6X. This occurs when the company raises its profile with investors by focusing on a fast growing market or better public relations. The effect is to raise the enterprise value of $1 million in earnings from $5 million to $6 million (compare to prior column). With no debt, the PE equity stake is $6 million, which is 20% more than the $5 million after the debt is paid off or 500% more than the value at acquisition.

- The "Grow Income" column shows the effect of growing income-earnings double from $1 million to $2 million. Since the multiple is 6X, that translates to $12 million in enterprise value.

Accomplishing all three steps-no trivial task-means that the PE firm grows the value of its position from $1 million to $12 million, a 12X or 1,100% return. [35]

A PE investor will negotiate the lowest valuation it can up front and the highest valuation at exit, like anyone else would. But it has ways to minimize its at-risk investment and more ways to grow the value of its stake than a VC or angel investor, thus it will evaluate a valuation differently.

Evaluating the Valuation of a Company That Uses the Fairshare Model

Does the Fairshare Model change how a company's valuation is assessed? You betcha (as they say in the Midwest)! That's it's raison d'etre (as they say in France) or reason for existence!

The premise, as you well appreciate by now, Dear Reader, is that it is very hard to come up with reliable valuation for a venture stage company. So, why have one? This was touched on at the end of chapter eleven. But, why make it as consequential as it is now?

In medicine, if we had an unreliable test for a condition where the treatment was consequential and also had a high chance of being wrong, there would be clamor for a better way. A better test. A way to delay imposing the treatment on the patient. Or a better treatment.

The similarity is this: absent a more reliable way to value a startup, shouldn't we explore ways to delay the partitioning of interests between those who provide ideas and labor, and those who provide capital? If you have made it this far in the book, you are clearly open to it.

So how should the valuation of a company be viewed when an issuer uses the Fairshare Model?

- As something that will change, possibly dramatically, based on the conversion rules and performance.

- As something set for strategic reasons, not because that's what it "should be" from an economic sense. [One might conclude this about valuation using a conventional capital structure.]

An issuer's strategic reasons for setting the IPO valuation where it does with the Fairshare Model will vary by constituency but they will overlap, as you can see below.

- IPO investors: Issuer is motivated to offer a low valuation designed to creating enough investor awareness and interest that the offering is fully subscribed in an expeditious manner (i.e., all new shares are sold fast).

- Secondary market investors: A low IPO valuation will promote a Black Friday sale mentality, which promotes secondary market trading. Ideally, the price of Investor Stock will climb, which is good for the issuer's pre-IPO and IPO investors.

- Pre-IPO investors: If these investors are long-term investors, they will not be not be bothered by the low IPO valuation. That's because a VC, the alternative funding source, would want a low valuation too. Not only that, it would require deal terms that could squeeze the other investors out. These benefits can mollify pre-IPO investors concerned about the low IPO valuation. Further inducement can come in the form of warrants on the Investor Stock or participation in the Performance Stock pool.

- Founders/Management: A high IPO valuation satisfies the desire for wealth and an ego boost. Here are factors that could make a Fairshare Model offering appealing to offset the allure of those factors:

- The management team defines the conversion criteria.

- If the team performs well, they can own more of the company's tradable stock than they would if the money came from VCs.

- Their willingness to be capital structure innovators will create popular interest in the company and its leadership team. That will create awareness and interest in their company that can pay dividends in virtually every aspect of the business.

Closing thoughts

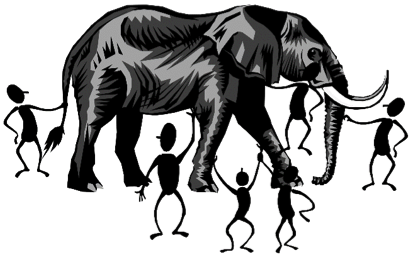

How should one evaluate a valuation? It's a bit like evaluating a piece of art-opinions vary. The question reminds me of a poem by the 19th century American poet John Godfrey Saxe called The Blind Men and the Elephant. Inspired by fables from several religious traditions in the Indian subcontinent region, it illustrates the limits of analytical thinking and the risks of fragmented knowledge.

Saxe tells of six learned men from Indostan "who went to see the Elephant, though all of them were blind." The one who feels its tail concludes that the elephant is like a rope. The one who feels its side proclaims the beast is very much like a wall. The one that grasps its feet declares it is clearly like a tree. The one that touches the ear says it's more like a fan. The one that strokes the tusk concludes a spear is more apt while the one that encounters its trunk insists that the elephant is like a snake. The poem concludes:

And so these men of Indostan

Disputed loud and long,

Each in his own opinion

Exceeding stiff and strong,

Though each was partly in the right,

And all were in the wrong!

The story suggests how to assess a valuation; consider multiple perspectives, including the possibility that they may be wrong. This moral leads one to question the appeal of a conventional capital structure, which demands certainty about the value of future performance.

Dear Reader, there is much advice available on how to evaluate a valuation. I hope this chapter encourages you to learn more. Do your research, seek out the most knowledgeable people you can, then find other sources. Persistently ask "How?" and "Why do you think that's the best way?"

By the way, the way I evaluate a start-up valuation is to consider the likelihood that the Next Guy will pay more. This assessment hinges on external factors as well as internal ones. That is, the general state of the markets, the space that the company operates in, the projections and the risk associated with them. In particular, I pay attention to how long before the company will need more money. I look at how much it has now, how much it wants to raise and estimate how many quarters it will last. Finally, I try to imagine how attractive the company will look then. Also, the probability that current investors will invest more and likelihood that another company might acquire it.

Onward

The next chapter, the final one in the valuation section, presents a case for a valuation disclosure requirement in offering documents.

[13] Bernstein, Peter; Capital Ideas, page 117-118

[14] All quotes and many of the ideas in this section about intrinsic value are from pages 149 to 162 of the 1992 book Capital Ideas: The Improbable Origins of Modern Wall Street, by Peter L. Bernstein, The Free Press

[15] It is convenient to use net income as a proxy for cash flow, but there is a difference. Non-cash related expenses include the accrual of liabilities and the amortization (depreciation) of assets. Investors care more about cash flow-cash generated or consumed-than income as defined by accounting standards.

[16] Not all investments are designed to produce future cash flows. An investment in research or art come to mind. So too, an investment in infrastructure or preventative maintenance.

[17] If there is a significant difference between net income and cash flow, cash flow is used.

[18] Ouija is a game played with a board that has letters and numbers on it. In a spiritual séance, players place their fingers on a small heart-shaped slider, taking note of where it points. Supposedly, the slider is guided by mysterious spirits that know the answer to questions the players ask.

[19] "Why Uber Might Well Be Worth $18 Billion", by Andrew Ross Sorkin, New York Times, June 9, 2014 http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2014/06/09/how-uber-pulls-in-billions-all-via-iphone/

[20] "With New Investment, Lyft Valued at $275 Million", by Evelyn M. Rusli, May 23, 2013, Wall Street Journal http://blogs.wsj.com/digits/2013/05/23/with-new-investment-lyft-valued-at-275-million/

[21] "Lyft Raises $250 Million Series D To Fight The Car Wars", by Jeff Bercovici, April 2, 2014, Forbes, http://www.forbes.com/sites/jeffbercovici/2014/04/02/lyft-raises-250-million-series-d-to-fight-the-car-wars/

[22] Kilpatrick, David; "The Facebook Effect: The Inside Story of the Company That Is Connecting the World", 2011, Simon and Shuster, page 124-125.

[23] http://videos.gust.com/pages/john-huston

[24] Ramsinghani, Mahendra; "The Business of Venture Capital"; 2011; Wiley, page page 182-183

[25] Ibid, page 183

[26] There are limits to this analogy. The value of a sports franchise is be based on revenue and profitability, not its winning record.

[27] Ibid, pages 180-183

[28] Cain, Susan; "Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World that Can't Stop Talking", Crown (2012), page 45-46, 53-

[29] "Angel Investing", by David S. Rose, Page 94

[30] Angel Investing", by David S. Rose, Page 96

[31] Shark Tank episodes are on YouTube

[32] ($300,000 investment/20% ownership) - $300,000 investment = $1,200,000 pre-money valuation

[33] ($300,000 investment/51% ownership) - $300,000 investment = $288,235 pre-money valuation

[34] Tip of the hat to Brad Winegar of Salt Creek Capital, a leading private equity firm in the San Francisco bay area, for providing this presentation.

[35] 1,100 percent return = [$12M value - $1M investment ]/$1M investment)

Karl M. Sjogren *

Contact Karl Sjogren is based in Oakland, CA and can be contacted via email or telephone:

Karl@FairshareModel.com

Phone: (510) 682-8093

The Fairshare Model Website

A native of the Midwest, Karl Sjogren spent most of his adult life in the San Francisco Bay area as a consulting CFO for companies in transition—often in a start-up or turnaround phase. Between 1997 and 2001, Karl was CEO and co-founder of Fairshare, Inc, a frontrunner for the concept of equity crowdfunding. Before it went under in the wake of the dotcom and telecom busts, Fairshare had 16,000 opt-in members. Given the rising interest in equity crowdfunding and changes in securities regulation ushered in by the JOBS Act, Karl decided to write a book about the capital structure that Fairshare sought to promote….”The Fairshare Model”. He hopes to have his book out in Spring 2015. Meanwhile, he is posting chapters on his website www.fairsharemodel.com to crowdvet the material.

Material in this work is for general educational purposes only, and should not be construed as legal advice or legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances, and reflects personal views of the authors and not necessarily those of their firm or any of its clients. For legal advice, please consult your personal lawyer or other appropriate professional. Reproduced with permission from Karl M. Sjogren. This work reflects the law at the time of writing.